Struggling to Rise to the Political Moment

Michael Peel on how the two main parties must confront long-term problems and ditch fantasies of restoring past greatness if the UK is to adapt to the world as it is now.

The general election campaign is struggling to rise to the political moment – and this promises trouble for whoever wins.

Both the Conservatives and Labour are ducking pressing questions that will face them in office about the profound ways in which the UK and its place globally are changing.

They have little to say about big domestic demographic shifts that will require a rebalancing of economic and social priorities. Nor are they talking much about how Britain will sustain and project itself in an international arena of growing commercial competition and rising political tensions.

The two main parties have self-evident tactical reasons for avoiding conversations with the public about forbidding long-term problems that will be hard to solve. But they will have to confront these if the UK is to adapt to the world as it is, rather than cling to fantasies of restoring past greatness or once-benign economic conditions.

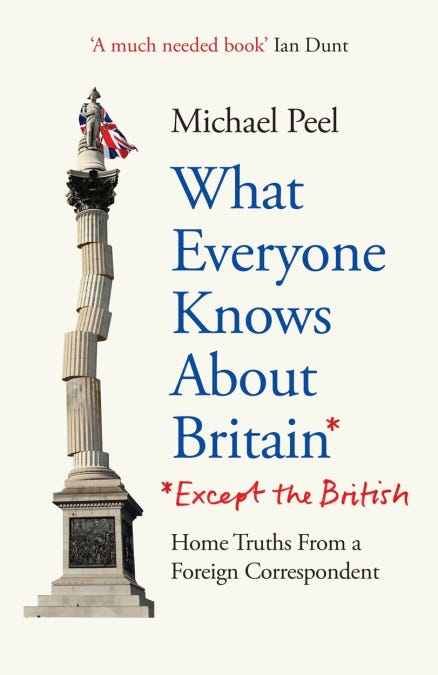

These denialist tendencies are intense in Britain, as I learned during research for my new book What Everyone Knows About Britain* (*Except the British). They are built on a deep bedrock of national myth-making about indomitability, self-reliance and integrity. The rupture of Brexit stemmed partly from feelings like these – and it has increased the dangers they present.

British politics seems in a fundamental respect caught in a similar trap to that gripping other rich nations, especially in Europe. The rise of popular disillusionment and the parties that draw strength from it reflects in part a refusal to acknowledge properly the end of western post-war dominance. Mainstream politicians present the period of prosperity and power known evocatively in France as the “glorious thirty” years as an aspirational norm, rather than a historical anomaly.

One transformation rarely given due prominence by British politicians is the fundamental impact on the economy and public spending of the aging population. In the 40 years to the early 2020s, life expectancy rose from 76.8 years to 82.6 for women and from 70.8 to 78.6 for men. Meanwhile, the fertility rate in England and Wales fell to just 1.49 children per woman in 2022 – way below the population replacement rate of roughly 2.1.

The narrowness of political arguments over migration show how neither party is publicly grappling with the magnitude of this shift. The working population threatens to shrink while demands for health and social care for older people rise. An aging nation can either supplement its population through immigration, or pare back aspects of its economy and public services to reflect a dwindling labour force. The Conservatives have barely begun to address this point over the past 14 years; Labour’s implication that economic growth will finesse such choices seems unrealistic.

A similar silence surrounds tax policy at a time of pressing spending requirements, including to upgrade decaying infrastructure. The Conservatives are still promising tax cuts. Labour has ruled out using the big levers of raising corporation tax, national insurance or levies on income, capital gains and wealth. Voters don’t seem to believe the parties, perhaps intuiting the underlying social truths the politicians mostly avoid. Whoever is in power will need bigger plans if they are to make a deeply unequal country fairer.

The public seems similarly ahead of the politicians in its willingness to consider the impact of Brexit. While the Tories and Labour barely talk about it, opinion polls have for some time suggested a clear majority see leaving the EU as a mistake in hindsight. The Conservatives who oversaw Brexit have almost nothing to say about this, while Labour offers the prospect of only small tweaks to UK-EU relations.

Brexit is significant in itself, but its wider importance is that it has revealed a damaging misperception about the UK’s ability to go it alone. Armed conflict in Ukraine and the weaponization of commerce between China and the US have highlighted the importance of European regional-scale institutions, however imperfect. It pays to be in the room with your neighbours: if you are not, they might make decisions that affect you but you don’t like.

At the same time, the UK and other European nations have yet to reckon fully with their declining relative economic importance. Other, sometimes much bigger, countries have risen around them. Many are loosening shackles imposed on them by colonial occupation – in some cases by Britain – or their own internal conflicts. They are highly competitive and even dominant in a growing number of spheres, from information technology and drug manufacture in India to electric vehicles in China.

The sorry story of Power by Britishvolt, the lithium ion battery maker that went into administration last year, betrayed a failure to adapt to those new realities. The UK’s next rulers need a sharper focus on areas of innovation and services where it has demonstrable strengths. The country still has an enviable science and technology base – though the funding crisis in higher education and official hostility to immigration risk endangering that.

Britain’s political discourse still doesn’t appear to accommodate adequately how the nation’s island status has transformed from historical strength to modern weakness. What was an invaluable protection against invasion as recently as the last century is a vulnerability in an age of resource scarcity and trade wars. Now Britain is uneasily reliant on imports in crucial resource areas from food to critical minerals needed for high-technology equipment. It doesn’t help that it has put up extra trade barriers to supplies of some of these and other important materials from its nearest neighbours.

The tale of North Sea oil encapsulates a sense of lingering British establishment complacency. It is revealing how rarely this is discussed politically as a cautionary tale to learn from. While nations such as Norway and Kuwait have massive, dedicated funds from their energy wealth, the UK under both main parties poured its money into the general revenue pot. It part-funded an era of tax cuts and right-to-buy housing subsidies under the Conservatives, helping power them to three election victories in 1983, 1987 and 1992. How Britain could do with that cash now to help meet its pressing investment needs.

A country whose leaders avoid sufficiently acknowledging both past shortcomings and historic global changes risks harming itself. Keir Starmer’s statement that politics should “tread lightly on people’s lives” is fine as a rejection of Conservative-induced chaos, but Labour needs to encourage public engagement, too. The old truism about war applies to politics: you may not be interested in it, but it is interested in you.

Some comfortable commentators, particularly on the political right, have already begun to claim that the UK is doomed. This is a travesty of how much the nation still has going for it – partly thanks to the legacy of a still barely reckoned-with imperial history.

Britain’s next leaders need to blend greater honesty about their task with higher ambitions and more modesty about the country’s international standing. It’s a sensibility largely missing in the early election exchanges. It is time for our parties to show that the British self-image of ingenuity, versatility and resilience in tough times is true.

Michael Peel is a Financial Times journalist. His book What Everyone Knows About Britain* (*Except the British) is published by Monoray.

This situation will remain as long as we have dishonest politicians like Johnson and Farage plus a gaggle of others, backed by an even more dishonest media, with an ill informed and gullible populace.

Damning but hopeful. I would like Brexit to work out for us though. Closer relations with Europe, outside of Europe.