Digital Gangsters: How Brexit Campaigners Harvested Your Data

In an exclusive extract from his book, Ian Lucas reveals how Cambridge Analytica quietly harvested personal info in order to drive Britain out of the EU

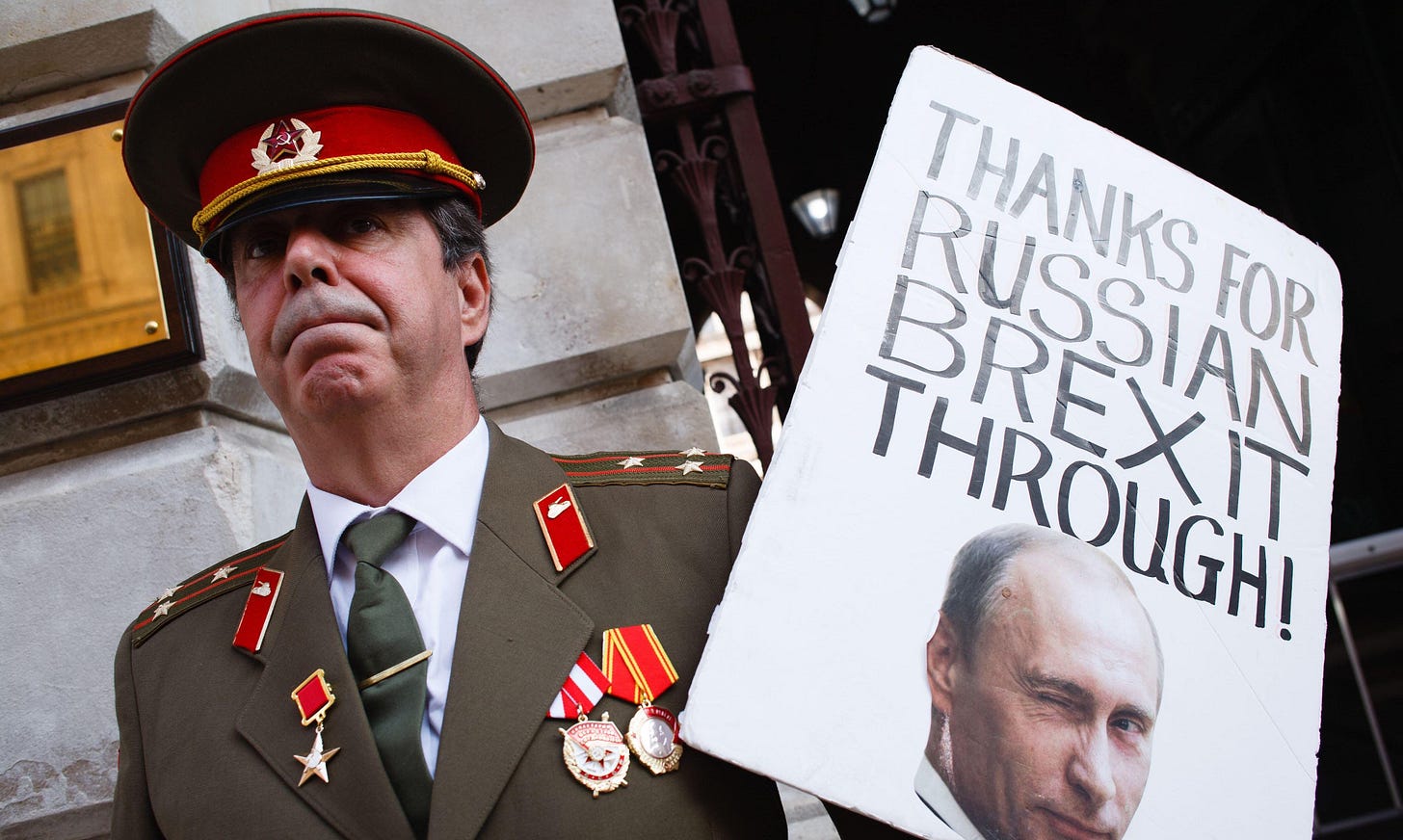

The recent storm of criticism around Labour’s digital attack ads on Rishi Sunak was ironic. After all, such ads were the weapon of choice for Dominic Cummings and the Vote Leave campaign in the 2016 Brexit Referendum. Their success, and the close personal connections between the Leave campaigns in the UK and Steve Bannon and the Trump US Presidential campaign led to their successful deployment in the US later in 2016. These facts were highlighted in the UK Parliament as long ago as 2018 and examples of the ads used in the “Leave” campaign were published by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee Inquiry.

In the febrile context of the Brexit vote aftermath, there was little appetite to highlight the impact of the digital ads used, especially by a Conservative Government dedicated to implementing the declared result. The same newspapers outraged recently by the Labour ads were silent in 2018.

The effectiveness of the ads was increased by their targeted deployment using personal data collected on social media. I highlighted the importance of these issues in my book Digital Gangsters, building on the work of the House of Commons Select Committee, of which I was a member.

Digital Gangsters

I think I was getting under Alexander Nix’s skin. Nix, the Chief Executive of Cambridge Analytica, was giving evidence to our Committee in Parliament on 27 February 2018, a couple of weeks after we had come back from New York and Washington. He is a dapper, slim man and was smartly and soberly dressed, looking more like a civil servant than a salesman. He appeared at ease, initially confident and very willing to be discursive in his answers to questions. He was, however, less happy to be challenged on his evidence.

One of the recurrent puzzles of the “Fake News” Inquiry was Nix’s repeated insistence that Cambridge Analytica was not involved in the Brexit Referendum. Nix maintained to Damian Collins that “No company that falls under any of the group vehicles in Cambridge Analytica or SCL or any other company that we are involved with has worked on the EU referendum.” (my Italics)

It was just about possible for Nix to claim this, as it is not clear that in February 2018 there was still a continuing relationship between Cambridge Analytica and AggregateIQ. AggregateIQ (AIQ) was a small Canadian data firm that was the main focus of Vote Leave’s digital spending in the Referendum campaign. In 2016, Cambridge Analytica had certainly been “involved with” AIQ. And AIQ executive Jeff Silvester confirmed later in oral evidence to the Committee that for a period before 2015 Cambridge Analytica had been AIQ’s only client.

There may well have been presentational reasons for Cambridge Analytica to claim distance from AIQ, even in 2016. Whilst the two businesses may not have been the same, they were intimately connected. The personal animosity between the two main Leave campaigns, Leave.EU and Vote Leave, was such that it would have been more comfortable to emphasise their distinctness than their closeness if the two companies were trying to represent both Leave campaign organisations.

It seemed to me that there were two unravelling threads we had pulled on in our US evidence sessions which could be pursued with Nix. Firstly, there was the question of Facebook and its use in elections. Secondly, what was the involvement of Cambridge Analytica and how did it obtain and use data for campaigning organisations? Later in the Committee’s Inquiry, it became clear that the answers to these questions were intimately linked.

The Committee had been helped considerably to this important conclusion by two earlier pieces of work by others.

In December 2015, the Guardian journalist Harry Davies had published an article about campaigning in the primaries for the US Presidential Election. It suggested, for the first time, that Cambridge Analytica had been using Facebook data to campaign on behalf of Republican candidate Ted Cruz. What was crucial was that this was “observed” data, including a media user’s browsing history and clicks on a webpage. It went way beyond traditionally collected canvassing data.

Next, in February 2017, US citizen and academic David Carroll had had the very bright idea of making a Subject Access Request under the UK Data Protection Act for sight of the information which Cambridge Analytica held on him as an elector in the US Presidential Election. This information would not be available to him under US law, but UK regulation would allow him to secure it. This is an important example of how legal regulations can facilitate access to information for individuals in a way that internal business arrangements cannot.

Nix did not want to talk about these issues. He was giving evidence, it seemed to me, because he wanted to be in Parliament to boost the developing profile of Cambridge Analytica still further. At that time, the world of politics was still in shock following Donald Trump’s election, struggling to work out how something so surprising had happened. Many were curious, perhaps beguiled, by the discussion beginning about the influence of online campaigning.

Preparing for the session with Nix, I had watched him present at a “Marketing Rockstars” event in Hamburg in 2017. Wisely, our Committee briefing on Nix from our research guide Jo Willows had urged us to watch the YouTube video in full. The event felt like a rock concert, hosted in what appeared to be a sports hall before an audience of thousands. Nix was comfortable onstage, explaining the pseudo-science of Cambridge Analytica in front of huge screens, focusing on the psychological assessment of users online and the mechanics of targeting advertising in both consumer goods and politics.

It struck me that Nix was much less comfortable talking about the process of how he was collecting the information that enabled him to do the targeting, an issue some shrewd members of the “Online Rockstars” audience wanted him to talk about more. This was an issue Harry Davies had explored to telling effect in his journalism.

Just how was Cambridge Analytica getting all this data from people?

I, along with other Committee members, wanted Nix to talk about collection of data in the evidence session. My own thoughts on the matter were conditioned by my legal background. I wanted to know who owned the data which Cambridge Analytica was using. Had people agreed to let them use it? Damian Collins’ mind was working the same way. He asked:

“You do not have access to data that is owned by Facebook.”

Nix replied: “Exactly.”

To Rebecca Pow, Nix was explicit again:

“We do not work with Facebook data, and do not have Facebook data.”

This was not true, though we did not have the evidence to know that at the time. On the contrary, far from Facebook not sharing its data, for many years it had agreed to work with different businesses and individuals who were permitted to use Facebook data to help develop their own applications. These people were known as “developers”.

Facebook’s relationship with developers was explained to the Committee at a later session by former Facebook employee Sandy Parakilas:

“When you connect to an app, you being a user of Facebook, and that app is connected to Facebook there are a number of categories of these apps, including games, surveys and various other types. Facebook asks you, the user, for permission to give the developer, the person who made the app, certain kinds of information from your Facebook account, and once you agree Facebook passes that data from Facebook servers to the developer. You then give the developer access to your name, a list of the pages that you have liked and access to your photos, for example.

“The important thing to note here is that once the data passed from Facebook servers to the developer, Facebook lost insight into what was being done with the data and lost control over the data. To prevent abuse of the data once developers had it, Facebook created a set of platform policies—rules, essentially—that forbade certain kinds of activity, for example selling data or passing data to an ad network or a data broker.” (DCMS Committee, 21 March 2018, Question 1188)

One of those developers, as Harry Davies had told us in his article for the Guardian back in 2015, was Aleksander Kogan, a Cambridge University academic who had worked with Cambridge Analytica from 2014. Davies had described Kogan’s process for collecting Facebook data, flatly contradicting what Nix was now saying:

“Kogan established his own company in spring that year (early 2014) and began working with SCL to deliver a ‘large research project’ in the US. His stated aim was to get as close to every US Facebook user in the dataset as possible.

“The academic used Amazon’s crowdsourcing marketplace Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to access a large pool of Facebook profiles, hoovering up tens of thousands of individuals’ demographic data – names, locations, birthdays, genders – as well as their Facebook ‘likes’, which offer a range of personal insights.

“This was achieved through recruiting MTurk users by paying them about one dollar to take a personality questionnaire that gave access to their Facebook profiles. This raised the alarm among some participants, who flagged Kogan for violating MTurk’s terms of service. ‘They want you to log into Facebook and then download a bunch of your information,’ complained one user at the time.

“Crucially, Kogan also captured the same data for each person’s unwitting friends. For every individual recruited on MTurk, he harvested information about their friends, meaning the dataset ballooned significantly in size. Research shows that in 2014, Facebook users had an average of around 340 friends.”

(The Guardian, 11 December 2015)

So, Cambridge Analytica had in fact been working with Kogan to collect Facebook data as long ago as 2014 and had been working with the Cruz campaign in 2015 in the US Presidential Election primaries. The data collection had not just been of observed data from consenting Facebook users, but also of observed data from their Facebook “Friends”, who knew nothing of Kogan, had not been contacted by him and could not possibly have consented to their data being used in this way, because they knew nothing about it.

The collection of data from Facebook “Friends” by Facebook had already got them into trouble.

As long ago as 2011, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) had alleged that Facebook had “deceived consumers by telling them they could keep their information private, and then repeatedly allowing it to be shared and made public.” One such deception was the alteration of its website in December 2009 so certain information that users had designated as “private” – such as their Friends List – was made public.

A settlement was reached by Facebook with the FTC that “consumers’ affirmative express consent” would be required before they could make any changes to terms and conditions that override consumers’ privacy preferences. Clearly, third parties, such as Friends, should not have had their data collected without their knowledge or consent.

So, the very data misuse that was reported in 2015 had already been the subject of regulatory action against Facebook by US regulators in 2011 and was happening again.

Here was Nix denying any use of Facebook data and making no reference to Kogan, Kogan’s company GSR or its agreement with Cambridge Analytica, or any connection between use of Facebook data and Cambridge Analytica.

Similarly, in the evidence session Washington DC, Simon Milner and Monica Bickert of Facebook had denied that there had been use of Facebook data by Cambridge Analytica, despite it being put directly to them. In fact, Facebook knew well that there had been use of its data by Kogan and GSR, knew also that that data had been used by Cambridge Analytica in Ted Cruz’s primary campaign and said, when challenged later, that they took this sharing of their data very seriously. Yet in February 2018 Milner and Bickert denied to the Committee that it had even taken place.

With the benefit of hindsight, the Committee ought to have explored Davies’ 2015 article in more detail with Milner and Bickert of Facebook and with Nix during those February 2018 sessions. However, we had little background information about the data used by Cambridge Analytica and did not know just how true Harry Davies’ article was.

One of the recurring challenges for Committee members is the complexity of the relationships between the tech companies and developers and the way that data was used by them. My view was that if I agreed to use Facebook services and share my data with them, I should know the purposes for which that data was being used. I had no idea that my use of Facebook was being used for political campaigning.

David Carroll put it well to the Committee:

“The company (Cambridge Analytica) says that it uses our commercial behaviour data to link it to our data file and then make these political models. So that is why it becomes so important to understand the sourcing, because if it is the websites we visit, the products we buy, the television shows we watch, et cetera, that is then used to determine our likelihood to participate in an election, the issues that we care about most. People don’t understand that their commercial behaviour is affecting their political life.”

(DCMS Committee, 8 February 2018, Question 599)

Facebook never explained this. Though regulation of data use was far more “light touch” than regulation in other areas, even that straightforward regulation was being breached. Facebook users had not consented effectively to use of their observed data for political campaigning. They did not know it was happening. And how could Facebook “Friends”, effectively third parties, possibly have consented to use of their data in political campaigning?

Facebook was less interested in the privacy of Facebook users than in expanding its number of users, as Sandy Parakilas described:

“The way I would characterise it is that the unofficial motto of Facebook is, ‘Move fast and break things’. Most of the goals of the company were around growth in the number of people who use the service. At the time on the platform team, it was about growth in apps, growth in developers. It was very focused on either building things very quickly, getting lots of people to use the service, or getting developers to build lots of applications that would then get lots of people to use the service.

“I think it is worth bearing in mind that some of the most popular apps had hundreds of millions of users. They had huge scale. I cannot remember specific apps, but I believe that some of those apps asked for friend permissions, so a huge amount of data was being pooled out of Facebook as a result. The volume of data that was being pooled as a result of that permission was a concern to me.”

(DCMS Committee, 21 March 2018, Question 1208)

Exchange of data between Facebook and developers was, therefore, an essential component of Facebook’s system and its success. In fact, as we discovered later, it was the jet fuel that enabled Facebook to accelerate further expansion: as Kogan himself was to tell us, this exchange of information, without the consent of most Facebook users, was not only happening but was in fact the main driver of Facebook’s phenomenal growth.

Alexander Nix was very keen to distance himself from Facebook and use of its data when he first gave evidence to us. That is why he told us nothing of Kogan.

Nix was also determined to deny connections with Leave.EU. Damian had established early in the hearing that this was Nix’s position, but it did not seem to square with other evidence. Cambridge Analytica itself had put out a statement early in the Referendum campaign that it was working with Leave.EU and had even shared a public platform saying so. In his book, The Bad Boys of Brexit, Arron Banks, a leading figure of Leave.EU, also said: “We have hired Cambridge Analytica...”

Yet both Nix and Banks denied to the Committee that Leave.EU and Cambridge Analytica had worked together. It was almost as if they had agreed this as a line.

I looked continually for written evidence of an agreement between Cambridge Analytica and Leave.EU but there did not appear to be one. What did become clear, however, was that there was a series of close personal links between employees of Cambridge Analytica, its parent company SCL and the organisations that were campaigning to leave the EU, both Leave.EU and the official Leave campaign in the Referendum, Vote Leave. The online political campaigning world was a small one and personal connections were very important; more important, it was to become clear, than formal contractual relationships.

It has also become clear that both the official Vote Leave campaign and the Leave.EU campaign were using micro-targeted messaging to a very large extent in the Referendum and that both organisations had close contacts, at the least, with the intimately connected data campaigning businesses AggregateIQ and Cambridge Analytica respectively.

Concerns had been expressed even during the Referendum campaign itself about the truth of the Leave campaign’s messages, but in February 2018 these concerns had not developed sufficiently to prompt widespread questioning of the Referendum result.

The validity of the Referendum was, in 2018, a subject that the main players in UK politics did not want to discuss.

The 2017 General Election position of both the Conservative and the Labour Party was that the UK was leaving the EU. Though all the DCMS Committee members, including me, had supported Remain in the Referendum, most now supported the front benches of their party in agreeing to leave. Earlier in 2017 I had voted in favour of commencing the process of leaving the EU, by invoking Article 50 of the EU Treaty, and I believed that it was inevitable that it would take place.

I knew that if the Referendum result were challenged openly by the Committee, it would be seen as an attempt to keep the UK in the EU. It did not seem to me at that time that this was a realistic position for the Committee to adopt and, at that point, I had not seen enough evidence to make me call into question the validity of the Referendum result.

My own position on the EU was nuanced at the time. It was too nuanced for most of my constituents in Wrexham. There appeared to be growing polarisation in the town, increasingly reflected on Facebook and Twitter.

Throughout the years following the Referendum, I also received a steady stream of emails on the issue of the EU. Mostly, they expressed polarised views. Either the writer wanted me to “respect the decision of the people of Wrexham” and leave the EU or they wanted me to vote to remain in the EU. Regardless of how many times I pointed out that there were different types of arrangements for leaving the EU, the “Leavers” wanted to leave and the “Remainers” wanted to remain. Both positions were absolute. I stood in the middle of the road, being run over repeatedly.

The position was the same online. On Twitter and Facebook, it was posted that I was doing “everything in my power” to frustrate the view of “the people of Wrexham”, ignoring the fact that I had voted to trigger Article 50 when my Labour Committee colleagues, Jo Stevens, Chris Matheson, Paul Farrelly, and Julie Elliott had all voted against.

Though there were tetchy moments in the session, Alexander Nix survived the Committee largely unscathed. But we had placed his evidence on the record and, quite soon, we would be seeing a chastened Alexander Nix.

Political Advertising - what now?

The vital question today is, will Labour commit itself in Government to regulating political advertising online? Firstly, factually inaccurate ads should be banned just as factually inaccurate ads in any other area are disallowed by the Advertising Standards Authority. Secondly, there should be financial limits imposed on political advertising, not just in pre-election periods, but at all times. The present “arms race” in political advertising encourages political parties to spend huge amounts of money and to accept money to facilitate the spending from dubious sources.

OFFER: Buy a copy of Ian Lucas’s Digital Gangsters: The Inside Story of How Greed, Lies and Technology Broke Democracy for 30% off the normal price in our online shop.

I’d argue that job 1 is to truly understand these tech companies. As a new Labour Party member I’m appalled at the lack of tech understanding. That in turn allows US marketers an open goal through which to knock anything they like past U.K. politicos. They are skilled at this stuff. As I was reading your story, I got where you are coming from but found myself screaming at the screen: ‘you’re asking the wrong questions.’