Try Fractal Travel this Holiday Season

The world cannot survive the modern obsession with mass tourism and air travel, but during the pandemic lockdowns, Peter Jukes discovered an alternative…

In this article exclusive to the September print edition, Byline Times’ executive editor finds hidden adventure.

Travel doesn’t broaden the mind – it narrows it. Spreads it thinly across the surfaces of things. You stay just long enough to tire of the sights, but never long enough to penetrate beneath them.

I wrote those lines, nearly 40 years ago, during a year-long period travelling through India. It wasn’t an original thought. By the early 80s, despondency at the promise of travel was a common refrain. Few evoked my suburban background as brilliantly as David Bowie, and in ‘Life on Mars’ he summed up the post-consumption tristesse of tourism: “See the mice in the million hordes, from Ibiza to the Norfolk Broads.”

Of course, I didn’t travel to India thinking of myself as a tourist, or a mouse. Back then, we’d distinguish ourselves from the multitude by calling ourselves ‘travellers’, and (en masse) visit out-of-the-way places using Lonely Planet guides. Our motto was the dictum of the Sierra Club: “take only photographs, leave only footprints”.

But photos fade, and footprints erode. Trekking in the Himalayas, the rocky mountainsides were already scarred by the tramp of backpackers. I’d hear fellow travellers complain about the rubbish already piling up at Everest Base Camp, but also admitting that – having climbed up to 15,000 feet – they were gasping for a can of Coca-Cola.

In the last 40 years, as tourism has globalised and grown, those footprints – amplified through safari vans in the Serengeti, cruise ships in the Venetian Lagoon, or diving boats over Pacific coral reefs – have a devastating, cumulative effect. And the less visible carbon footprints are even more damaging. Tourism accounts for 8-11% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council – more than the construction industry. Nearly a fifth of all total travel carbon emissions come from aviation and, if we continue on this route, without using less polluting forms of public transport or reducing emissions by choosing destinations closer to home – we’re on a flight to nowhere.

So travel not only narrows the mind, it tramps reality underfoot. However, I do have a solution, which could preserve the planet and still satisfy our urge for exploration: fractal travel.

The Crow and the Snail

I first discovered the possibilities of fractal travel during the long lockdowns of the pandemic.

With airports restricted, venues, gyms, restaurants and pubs closed, we were told to observe social distancing and exercise outdoors. For months then, the greatest journey I could make was around my local neighbourhood and my only chance of adventure – opening my front door and turning a corner.

I’m lucky enough to live in central London where every corner is a fast chicane between the past and the present, but – as we will see – fractal travel is certainly not limited to traditional tourist hotspots or historic city centres. And it wasn’t the famous monuments or avenues I went to explore, but the hidden back alleys, lost rivers and buried memories.

During those long lockdown walks, nursing sore knees creaking with inflammation after an early Covid infection, I was reminded of something I’d learned in my teens through long walks around the margins of a small county town: even the dullest, most ordinary objects look extraordinary when approached from another angle.

Take the Thames, that muddy, familiar old friend and the main route for my meanderings. For a start, it’s never the same. The Thames’ tidal range at London Bridge is a staggering 20ft twice a day. This constant ebbing and flowing reveals and conceals watergates, old wharves and jetties. Go down to a temporarily emerged beach and look closer still: the flotsam and jetsam of modernity mingle with Victorian ironware, medieval pottery and 17th Century clay pipes.

I can’t think of any other capital city, so far from the sea, which is so reliant on the tidal force of nature quite as much as London. If timed properly, a ship can drift in and out of the city at a rate of five or six knots (7 mph or 11 kph) just on the tides alone. Geography is destiny and the navigational fluke of the Thames helped make London the centre of a maritime empire (with its attendant navigational science) and the biggest port in the world. So many of the human accretions on its shore, from the observatory at Greenwich, past the docks, all the way up to Westminster, are explained by this renewable tidal powerhouse.

For almost two years then, guided by books such as Lara Maiklem’s Mudlarking and Tom Chivers’ London Clay, I rediscovered the obvious truth that the more you look, the more you see. I replaced extensive tourism with intensive travel; quantity with quality – the kind of microcosmic vision of William Blake’s “to see a world in a grain of sand”.

But this kind of fractal travel isn’t just underpinned by poetry or mysticism. It’s based on science.

The shifting shoreline of the Thames is like the classic ‘coastline paradox’ first explained by the mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson.

An example of the coastline paradox. If Great Britain’s coast were measured in 100km units, its length would be around 2,800km. However, if 50km units were used, the total length would be some 600km longer at around 3,400km. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A Quaker and ardent pacifist who had been a conscientious objector in the First World War, Richardson was intent on modelling the probability of wars, especially around border conflicts. He discovered that – whatever the territorial claims and counterclaims – even the actual length of international borders was often disputed. Between Spain and Portugal, the border length ranged from 987 to 1214 km, while the border between the Netherlands and Belgium varied between 380 and 449 km.

These variations, Richardson discovered, were not random anomalies, but hard-wired features of frontiers. A long-running sore between the US and Canada, for instance, over the fjords of the Alaskan panhandle, was becoming intractable because of a line in the original treaty setting the border at "a line parallel to the windings of the coast". All the tools of classic geometry were only making things worse. Using the highly indented coastline of Britain as an example, Richardson proved the coast gets longer and longer the smaller the unit of measure.

We understand this fractal dimension implicitly when we use the common phrase that a pub or shop is so far away ‘as the crow flies’. For a human, the distance travelled will be longer because of bends, corners and diversions in between. Think of the detours and obstacles a snail would have to overcome to travel to the same pub or shop: scale affects distance. But Richardson discovered something else – there is no finite limit to this effect. As you measure an irregular line in more and more detail, the length increases to infinity.

That might feel intuitively unremarkable, but the ‘Richardson Effect’ had a revolutionary impact on modern mathematics and geometry. The "coastline length turns out to be an elusive notion that slips between the fingers of those who want to grasp it", noted the eclectic Polish-born French-American mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, who picked up on Richardson’s strange observation and used it to develop his landmark ‘fractal geometry’.

For thousands of years, classic geometry had measured and manipulated lines, planes and volumes in three dimensions. Mandelbrot, a self-described ‘nomad-scientist’ with a refugee background, used the coastline paradox to prove reality was much more fractional and fractious than Euclid’s famous triangles, cubes and cones.

Classically, a single line has one dimension, a plane two dimensions, and a volume three dimensions. In traditional geometry, all regularities could be plotted in those dimensions using mathematically consistent formulas for angles, curves or ellipses. But Mandelbrot focused on irregular boundaries and shapes in nature that eluded three dimensions and helped break the mould.

In fractal geometry, for example, a coastline is too detailed to be explained in a one-dimensional line and sits somewhere between one and two dimensions – typically with a fractal dimension of 1.5. Lake shorelines typically contain 1.28 dimensions. This blurring and breaking of parameters applies to two-dimensional surfaces as well. Mandelbrot’s collaborator, Columbia University professor Christopher Scholz, applied fractal geometry to mountains and calculated that a typical boulder-strewn talus slope doesn’t have two Euclidean dimensions, but 2.6.

Again, this would seem obvious to weary mountain walkers, but the mathematics behind this ‘new vision’ of fractal geometry has all sorts of applications: in medicine, mapping arterial blood flows; or in engineering, predicting the friction between different materials.

As James Gleick explains in Chaos: Making a New Science, “fractal came to stand for a way of describing, calculating and thinking about shapes that are irregular and fragmented, jagged and broken-up shapes from the crystalline curves of snowflakes to the discontinuous dusts of galaxies”.

But what about fractal travel?

Home and the World

The idea that we cannot measure distance independently of scale is something we’ve all instinctively apprehended since we were very small.

For me, the first great adventure I can remember was the gradient of the stairwell in our small semi-detached 30s house in northwest London. The stairs terrified me in recurrent nightmares, no doubt because I fell down them when I was about three, with my lower teeth cutting through my bottom lip so badly that I needed stitches.

This led to the next big adventure: a trip to the local hospital. I’m not sure if it was on that occasion, or an earlier visit when I was admitted with double pneumonia, but I can remember getting in the back of an ambulance. More vivid still is the memory of laying on my back on a trolley, watching the fluorescent lights pass overhead and peering up to see a grey institutional corridor which seemed to go on for infinity.

As we grow older and taller, our horizons get broader, spreading beyond the terrors of the stairs or the wasps around the rubbish bins to our streets and neighbourhoods. Infant adventure lurked behind every cul-de-sac and pelican crossing of my suburban environment; the trip to the high street to see Mary Poppins at the local cinema, or the purple door we passed on the way to school someone told me was inhabited by a witch.

My first tricycle ride was a near calamity, as I jumped on it right out of the toy shop and – before my mum could stop me – started careening down a slope towards a busy side road. Fortunately, a man in a green hat stepped in and prevented an accident. There were moral hazards too. A stray dog used to hang around the post box on the way to the clinic for polio vaccinations and check-ups. He wagged his tail, begging for attention. But if you patted him, he would just follow you everywhere, until you had to shoo him off or throw sticks to get him to leave you alone.

Incidents and accidents, good and bad, anything was better than that hospital corridor of remorseless infinity. Unfortunately, it was never very far away. In fact, it was just under my feet.

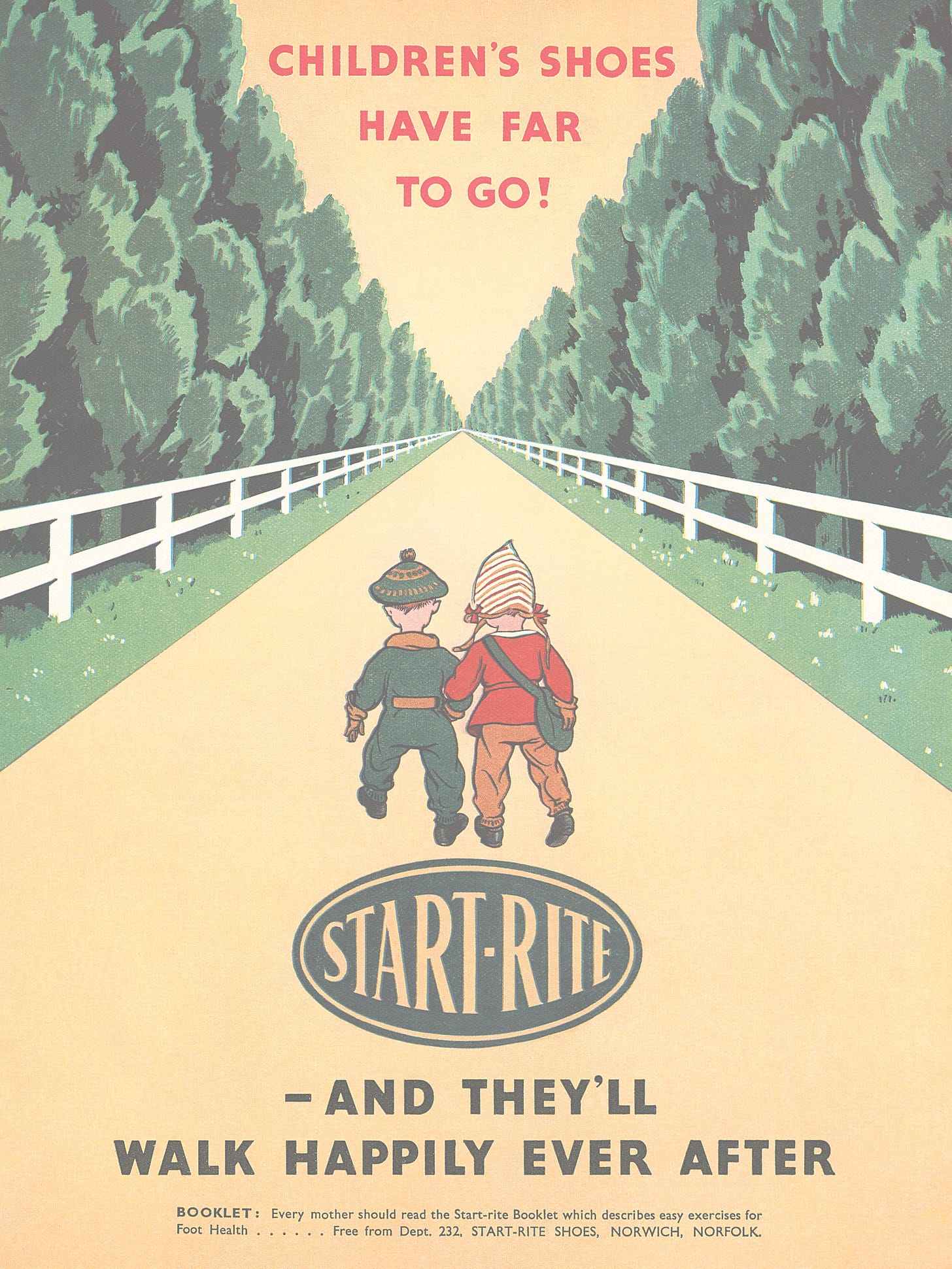

The London Underground of the 60s was crowded and noisy, with fag ends stuck in the rutted floors of the smoking carriages. To alleviate the trapped feeling, I’d pretend the darkness through the windows was outer space and I was on a rocket to the moon. But getting out on the Underground platform, any illusion of movement would soon go: the station was just like the one we’d just left. And across the Tube in those days were ubiquitous Start Rite shoe ads: two Dutch children starting down an ominous conifer-lined path. Like the hospital corridor, the white palings formed parallel lines that converged in infinity. Whenever I tried to imagine how long I still had left at school, all I could see was myself trudging down it forever.

Start-Rite children’s shoes ad. Photo: Neil Baylis/Alamy

Thankfully, my horizons widened as we moved out of south Harrow to the fields and woods of the north London greenbelt. Though I was only six, I was soon allowed to roam during weekends and holidays at will (as long as we got back by tea time) and there was a new world of footpaths through the leafy suburbs, ragged copses and bits of farmland. With friends we’d spend days exploring empty houses, playing on scaffolding in building sites, riding our bikes around gravel pits, and watching the trains run under the footbridge. And that gave me an idea...

One day, aged about 10, I saved my pocket money and, with a friend, we travelled on the Metropolitan Line all the way (at least three stops) from Northwood to Chorleywood, described as "essential Metro-land" by the poet laureate Sir John Betjeman in his 1973 TV documentary on the new exurban ribbon development. Though there was very little to see in the faux-Tudor beamed shops of Chorleywood, I did find a chemist and made it all the way home with a plastic bottle of methylated spirit – not for some early alcoholic addiction, but to power my toy steam engine.

Adventure and disillusion, exploration and retreat. As puberty progressed, we used the backwoods and footpaths less and less for Second World War reenactments, and more for adult pastimes: smoking cigarettes, setting fire to fields, throwing fireworks – till a banger nearly took out my eye. We found pornographic magazines and used condoms on the road verges. Kiss chase became our favourite game in the playground. My last real memory of adventure in those greenbelt fields was one hot summer afternoon kissing Susan Hazard in the long grass.

By now, a wider world was calling. I always knew it was there.

One of the first things I can remember writing back in my first home when I was four or five was a scrawl on the inside cover of a book: “Retep Jukes, 73 Torbay Road, Harrow, London, England, the World, Universe”.

My first trip abroad at the age of nine to the Costa Brava opened my nose to new smells (the floor polish of Alicante airport), new sounds (the grating of cicadas) and new hidden histories. We took a donkey ride down to a chasm where old women, still dressed in black from the Civil War, were drawing water from a well, avoiding the Guardia Civil with their guns and pointy hats.

This was the beginning of my obsession with the Mediterranean and Europe (the culmination of which – a disastrous hitchhiking trip – I’ve described before in these pages). But it all really came to a head when I was 10 and, for a brief moment with some money, my parents told me we were going on a cruise around the Mediterranean that Easter.

I couldn't wait. I studied the cruise brochure every day, tracking each port and voyage, and looking up the highlights of every country we were destined to visit. I counted down the days until we left, and was so excited that the night before we were due to leave I couldn’t get to sleep. I couldn’t wait.

Then at some point in the middle of the night, it dawned on me. The cruise was about to happen. Tomorrow was almost here. And if it wasn’t long until we left for the cruise, it wouldn’t be long until we came back. My enthusiasm suddenly collapsed, like my bipolar dad’s bipolar swings between excitement and sullenness. I realised, to my horror, that there was nothing to look forward to.

I was back in that hospital corridor, staring at the Start Rite ad on the Underground. My future looked like the tunnel formed by two mirrors facing each other, reflecting the same repetitive image over and over until it disappeared into a meaningless void.

Time Travel

I reflect on these personal childhood experiences at some length because the human geography that evolved in the 20th Century – the polarisation between the exciting, incident-filled fractal spaces of adventure; and the repetitive and rectilinear routes to get there – has spread all over the world in the decades since.

We all want to get to that taverna on the Greek Island, the vineyard in Provence, that yoga retreat in Bali, the Casbah in Morocco, that club in Ibiza, to lose ourselves in the unpredictable encounters, smells and incidents that will follow.

But to make that journey, we are compelled to create uniform corridors, to bulldoze down the fractal natural world, and produce ever more lifeless frictionless spaces: check-ins and jetways, autobahns and flyovers, cruise liners and boarding passes, even the smooth limousines that whisk you off to the identical international hotel with its infinity pool.

In the search for the particular and vivid, we generalise and banalise it. Then, in the desire to escape the world we have created by our wanderlust, we seek even further transcendence, at an ashram in India or a space flight with Richard Branson and Elon Musk.

Fractal travel could solve this, not only by inspiring us to transcend less and ‘descend’ more but also by overcoming the source of much of our yearning: time.

Most of our travels are not just about moving location, but also an attempt to recover something we feel we have lost. And time is not different to the other three dimensions. It also has discontinuities and irregularities.

Venice in 2022. Photo: Peter Jukes

In his General Theory of Relativity, Albert Einstein first calculated that there is a continuum between the dimensions – he called it ‘space-time’ – which is distorted, some physicists now suggest, at a fractal level, by gravity. Whatever the complexities of astrophysics or subatomic quantum effects, we all sense at a cognitive level that time is not linear or continuous. It appears to freeze or flow depending on whether we are bored, absorbed in the moment, or facing a split-second decision. Much of the basic visual grammar of film and TV revolves around this intuition that time slows down or speeds up as our minds do the reverse.

Modernity has been dominated by the triumphal march of linear time. Premised on the idea of progress, our social conditions have been radically transformed by industrialisation and urbanisation, and our daily lives increasingly conducted under the cold, watchful eye of the mechanical clock. Churchbells, which might have summoned peasants from the harvest, were rapidly and suddenly replaced by the ‘clocking in’ of factories, train timetables, traffic lights and alarm clocks. No wonder we needed ‘free time’.

The mass tourism industry can be seen as a response to the spread and dominance of linear time over the last two centuries. For some, wilderness tours, white water rapids, perilous sports or sex on the beach is one way to break the oppression of the ticking clock. For others, history itself has been a destination, with heritage tours to Florence, Venice, Paris or London, providing another escape from the conveyor belt of industrial time.

That was certainly an impulse for me, brought up in the suburbia of the 60s. Having realised the future was a futile illusion, I turned to something else for my adventures: the past.

At first, it was a fictionalised past. As a young child I once got lost in the mothballed coats and dresses of my parents’ wardrobe and for a delirious moment thought I might have actually made it to Narnia. As a teenager, my reading shifted from science fiction books to historical fantasies, and the countryside allowed me longer periods to indulge in this kind of imaginary time travel.

Sometimes I would read all night and go for a dawn walk, crossing old orchards, graveyards and church lychgates, where I could pretend I was living in an older, better time. One early morning, I startled a heron by a river, and as it flew over my head for a moment I was convinced it was a pterodactyl.

Escaping to the past, of course, wasn’t an option for long. Even on those dawn walks, the early morning chink and whir of electric milk floats quickly reminded me I was still in the 70s. The new jostled against the old continuously – or discontinuously: a vandalised supermarket trolley next to the remains of an old water mill; a 50s aircraft rusting away at the verge of an airfield, not far from the remains of an abandoned village. When I kissed my first true love on the banks of an old canal, the roar of traffic was never far from the skyline.

In this irregular light, our rural and semi-rural areas are full of possibilities for fractal travel as much as our historic cities. The birdsong, often with its local dialects, comes and goes with the seasons. Look deep into a hedgerow, count the number of species per metre, and you can work out how old it is. Many of the lanes and field margins have not changed for centuries – some for millennia. The names of towns, villages and hamlets suggest which invaders – Roman, Angle, Saxon, Jute, Viking or Norman – took over or settled here. That’s the other side of leaving footprints – traces of human activity have shaped our landscape as profoundly as glaciation or rising sea levels. The tramp of feet over ancient trackways since the Iron Age created holloways – sunken lanes often shuttered into deep wooded tunnels – one of which gives its name to the district of Islington near the Arsenal stadium.

The past isn’t another country. It’s all around us.

That’s what I finally learned on the shores of the Indian Ocean, when I despaired of travel ever opening my mind. Though I had been awarded a scholarship to write about the British imperial legacy in India, part of my reason for choosing the subcontinent as a destination was secretly some impossible craving for another era – the pre-modern world before the steel rails of modernity had destroyed it. But, whatever longing I had for peasant, mercantile, medieval or Victorian life was quickly dispelled by the cities, towns and villages of India in the 80s.

Though the culture was completely different, you could at least get a glimpse of the kind of economic and social conditions described in Chaucer, Shakespeare, Balzac or Dickens. The tedium of infinite corridors and narrow minds existed there too, along with the desire to escape. And when I eventually came back home to Aylesbury one dull winter's day, I found my own small town past as exotic and strange as anywhere else I’d been.

In this way, travel can broaden your mind – if only by teaching you its limits.

Presence and Absence

So what did my long lockdown journeys really teach me about reality, given its fractal nature? Is it all just worlds within worlds, fragments and chaos? Is there some kind of guiding principle in all our spatial and temporal restlessness?

I would say there Is. For just as gravity underpins Einstein’s model of the universe, a powerful consistent force pulls us towards it on our travels: human presence.

As the tunnels of my childhood suggested, the future is an absence, a void. We may have dreams, maps, blueprints or cruise brochures to look forward to, but the future is a speculative corridor, rather like the liminal space between two mirrors. Those plans rarely survive first contact with reality. And if you’re in search of adventure, you wouldn’t want them to.

The only thing we know for sure is the present (as it turns into the past) or the past (as it re-emerges into the present). The German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin expressed this retrospective insight in a passage inspired by Paul Klee’s painting ‘Angelus Novus’. “This is how one pictures the angel of history,” Benjamin wrote. “His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.” Benjamin’s angel of history, conceived on the eve of war before he took his own life fleeing Nazi persecution, is appropriately cataclysmic. The angel “would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed” but the storm of progress is tearing it away.

In the stillness and silence of lockdown, with the belief in progress feeling like a long lost cause, I did find myself in quiet but constant dialogue with the dead.

A few yards from the entrance to my flat, a round plaque on the pavement records the names of 20 people killed when their bomb shelter was destroyed in September 1940 during the Blitz. Directly over the road is another memorial plaque, recalling that this section of railway arches used to be a Quaker graveyard. A hop back across the street, and during excavations for a new building, archaeologists discovered an Iron Age burial site in what used to be the marshes and riverine backwaters of the Thames. A 10-minute walk away is the Crossbones garden, a lost graveyard rediscovered when London Underground’s Jubilee Line was extended under Southwark in the 1990s. Its railings are covered by tributes, from all over the world, to sex workers and other historically marginal figures. More recently, right next door, preliminary works of a new development called the Southwark Liberty exposed the mosaic floor of a Roman ‘mansio’ or upmarket hotel catering for second and third-century couriers and officials visiting London.

This is another example of the fractal nature of time: we cannot move forward without also going back.

Virtually every time we try to build something new in London, we rediscover something old. Back in 1989, when writing my first book A Shout in the Street, I noted that the foundations of a new office block had exposed the remains of The Rose theatre, the great rival of Shakespeare’s Globe. To my astonishment (and the realisation of how old I am getting!), that tower block has just been rebuilt, with plans to extend the excavation of the buried playhouse and build a new visitor centre.

The deeper the impact of change, the more the past is exposed. Many of the words we now associate with innovation – such as ‘invention’ ‘originality’ or ‘radical’ – have roots in words that mean rediscovering something from the past. But it’s not artefacts that speak to us across the abyss of time and space, but people.

A century ago, the archaeologist and philosopher R G Collingwood concluded that history was all about this – trying to recreate the thoughts of those long gone. That’s why we go to the reconstructed Globe Theatre to see the latest Shakespeare revival – we are in effect at a seance, talking with the dead. And with so many monuments or statues or works of art, it’s a two-way process – the dead are trying to communicate to us.

Take the Temple of Mithras, a Roman religious site, first uncovered after the Blitz but discovered in much more depth after the recent construction of the Bloomberg Building on London’s Walbrook Street. One wall at the entrance is covered by a montage of artefacts, but then you have to descend, at least 30 feet, to the original Roman street level, to where the whole plan of the building has been excavated, built alongside a hidden river. It’s a mysterious, darkened space, semi-reconstructed through musical effects and lighting. It doesn’t try to tell you what the religious purpose of the site was – instead, it tries to evoke the experience while leaving the interpretation of its ultimate mysteries unresolved.

The Roman Mithras temple archaeological site restored by Bloomberg. Photo: Justin Kase z12z/Alamy

The past, built by humans as memorials, tries to talk to the future. And there’s so much more to be heard and understood.

If there’s one message I learned through my staycation tours it was that the past proves human resilience and our constant need to communicate meaning to each other, whatever the barriers. When facing one of the most chaotic and authoritarian governments of my lifetime, or the very real threats of the climate emergency, every stone and plaque spoke of not retreat but advance; of confronting reality rather than escape.

London, like most vibrant cities, isn’t actually built by state edict, royal decree or corporate plan. From the docklands of the east to the residences and hotels of the west, the very fabric of the city has been determined for the most part by individuals, groups or voluntary associations. Built speculatively by entrepreneurs, the warehouses around the river, named after the commodities that built London as a global commercial centre – Coriander, Cardamom and Cinnamon – are now renovated and turned to apartments, occupied by a diverse diaspora of backgrounds due to that same imperial history.

Even the remote and inaccessible parts of our religious heritage have provided the foundations of our secular welfare state and social services. Look up the old sanctuaries, almshouses and liberties of London, and you will find they have evolved into hospitals and universities, charities and refuges. Fire stations, libraries, and schools create the focus of most neighbourhoods. For all the imposing apartment blocks, most of the housing in a place like Southwark builds on the work of pioneering reformers such as Octavia Hill on Red Cross Street, or Alfred and Ada Salter in Bermondsey – a legacy of voluntary association and collective care which provides much more gravity and permanence compared to the constantly changing steel and glass frontages of the corporate world.

During lockdown, this sense of individual and community cohesion was what kept the city alive, the streets clean, safe and welcoming, and all those myriad ways people try to communicate with each other, across space and over time.

So next time you feel trapped by linear time and want to take a real break, don’t wait for your holiday. Do it now. Instead of looking to distant places for adventure and insight, look closer. The every day is fleeting. One small virus can empty the streets and turn our hometowns into something rich and strange. The real journey we still have to make is in our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world, and if we travel in that, it’s not our minds alone that will broaden, but everything.