Tragedy Then Farce: The Second Munich Betrayal

An edited updated extract from his essential book 'The Dogs of Mariupol' by Tom Mutch

Munich, Germany, February 2025

“You are lucky your country’s so far away from Russia,” Volodymyr Zelensky smiled as he looked me in the eye across the small wooden table in a musty room of the Bayerischer Hof Hotel, and the room erupted into laughter. I’d introduced myself as being from New Zealand, and he’d interjected halfway through my question with a line that had brought the house down. Despite the years of war, he remained quick-witted, with a charisma and easy charm that dominated a room without seeming to expend any effort.

The truth was that most people in my home country had forgotten about the war. I wanted a way to convince them to care.

“I have a lot of connections with Australian leaders and New Zealand leaders,” Zelenksy replied, “and I always say to them: Let’s take the element of North Korea. Is that more dangerous for us or for your country!” The North Koreans, he said, would be bringing advanced missile and drone technology back to their home country, and they could use it to wreak havoc if not stopped. He made a veiled reference to other potential actors who could stir conflict in the region; likely referring to the possibility of China launching a military campaign against Taiwan but not wanting to cause a further diplomatic incident when his country already had enough problems on the world stage.

“Wars are no longer a matter of distance,” he continued. There was nowhere that you could hide; it was an implicit swipe at the Biden administration, which had stressed the importance of keeping the battlefield confined to Ukraine. But with North Korean troops now seen on the battlefield for the first time, how could this still be the case? A new world disorder was coming, and the war in Ukraine was just heralding it, Zelensky told me. Considering that this Munich Security Conference was being heralded as the end of the post-war era of American leadership, I thought the Ukrainian President in excellent spirits. Stress and pressure seemed to invigorate him, not tire him. After months of Zelensky, the world’s most famous war leader, hanging over my work like a shadow, I was pleasantly surprised to find he lived up to the hype in person.

Donald Trump had just arrived in the White House, and his Vice-President J. D. Vance had given a speech at Munich castigating all European countries for what he saw as their lack of commitment to freedom of speech. The largest European land war since 1945, currently raging at full tilt a few hundred miles to our east, seemed uninteresting to him. Instead, US officials had attempted to coerce Zelensky into signing a deal that would give up $500 billion of Ukraine’s rare earth minerals. Neville Chamberlain had gone to Munich for his fateful meeting with Hitler at least genuinely desiring peace. The current US administration was behaving like a low-rent mobster shaking their war-torn ally down for protection money.

I tweeted what I suspected, based on what I’d seen – “Trump might have finally overplayed his hand here. Zelensky isn’t some career Washington pol he can troll with a funny nickname. He’s the world’s most admired war leader, popular at home and abroad. That is respect that none of Trump’s power or Musk’s billions can buy” – and attached a photo I’d taken of Zelensky looking into my camera two years ago in Kherson. My message struck the mood – in just over a day, it had over 4 million views, 15,000 retweets and 90,000 likes, by far my most popular post.

The Ukrainian President was not to disappoint and was soon involved in one of the most spectacular diplomatic rows of all time when he went to Washington DC and, during a press conference, got into a public row with Trump and Vance over aid to Ukraine. The three men began shouting over each other, and the meeting broke up with rancour as years’ worth of personal resentments poured out. Despite a public pledge to end the war ‘within twenty-four hours’, the United States began cutting off all aid, both military and humanitarian, and quitting intelligence sharing. It seemed shocking to Ukraine and confirmed some of the worst of the whispers that some had about the US effort. That it was convenient while they could use it to bleed Russia, but once they were bored of the conflict, they would cut their losses and move on. Much like how Russia used the Donbas merely to destroy and control Ukraine, the US had used Ukraine as a battering ram against Russia, with no thought for the well-being of the country itself. It was also a great wake-up call for Europe that there was no longer any prospect of considering the US a reliable ally.

It was to Zelensky’s credit, I thought, that he was standing up for himself and his country’s dignity on the world stage. He was facing pressure from Trump and Musk to resign, taking all the slander that their troll armies could throw at him, while still dodging missiles and shells from Putin’s real army.

I thought of the comparison of Zelensky’s courage with that of Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who was watching on, his facial expression suggesting he wanted to be swallowed by the couch. It was barely ten years ago that he’d given a barnstorming speech on the Senate floor calling for military aid to Ukraine after Putin’s annexation of Crimea. “This challenge is truly bigger than our partisan divides,” he had said to thunderous applause.

Now, for the last six months, we’ve watched as people in the Trump administration repeat Russian propaganda, excuse Russian war crimes, and Donald Trump has spoken earnestly of Vladimir Putin’s supposed desire “for peace” while his Russian counterpart slams missiles into civilian targets around Ukraine. I’m writing this now on my knee in a taxi, as I drive to the site of yet another horrific massacre – at least 14 people were killed in Ukraine last night after a huge drone attack. But with the world distracted by the ongoing war between Iran and Israel, it has barely made a flicker on the front pages. The carnage and murder here – because that is what driving a drone full of high explosives into an apartment building is – has become routine.

Trump seems to have to seen Ukraine as little more than a geopolitical real estate deal, with no understanding of just how difficult it would be to get Putin to stop his invasion.

Michael Kofman, who was at the Munich conference at the same time as me, had also just visited the Ukrainian front line. “Morale was worse in Munich than it was at the front!” he said. The war in Ukraine was far from settled, he said, and there was still much to play for.

Wars are fundamentally contests of wills. It isn’t just the balance on the ledger; territory gained or casualties suffered. It is who ends up imposing their will upon whom. This war will not be determined by the next thirty or forty kilometres of Donetsk. That’s not what this war is about. It is about Russia imposing its will on Ukraine. In order for the war to end on acceptable terms, it can’t be the imposition of Russian will that is so unjust that it negates the point of having fought the war in the first place. It has to pass this moral and emotional test; what did we fight this war, make all these sacrifices for?

European leaders were shellshocked, and their fears about America abandoning them had finally come true. In some ways, they only had themselves to blame. Ben Wallace had been scathing to me about the lack of preparation for serious conflict in Europe: “I can speak for my own and some others in Europe, it looks good at the front – but under the bonnet, ammunition stocks, maintenance, availability, reliability of our equipment and the readiness of our soldiers to go anywhere has been hollowed out for decades.” Vance had hit out at Zelensky for ingratitude, saying, “Have you even said thank you once?” on this trip. For many Ukrainians, the thanks should be the other way around. They had given up their nuclear weapons in the 1990s to make the world a safer place.

For Ukrainian politician and advisor Mikhailo Podolyak, this war is proof of concept that might can make right, and the only way to stand up to an aggressor is with force and bravery. The rules-based international order just won’t cut it anymore:

“Russia will pay for its crimes, but only if you are ready to go through to the end. Our example of bravery showed that it is possible to stand up against such giants as Russia. Ukraine proves that if you have a comparable number of weapons, you will effectively fight back and win. Ukraine proves that the value of life is a value, but if your children and your families are behind you, well, you have no choice. At last, in the twenty-first century, you also need to be able to defend yourself. If you don’t know how to do this, then someone will always come to rob, rape, kill or deport you or your kids, take away everything you had in seconds.”

No one had told the Ukrainians of their expected impending demise, however. After the brief cut-off of US aid and intelligence in March 2025, they continued fighting as normal and held back the Russians; although Ukrainian military sources claim that this was a contributing factor to them losing the town of Sudzha in Kursk, which I had visited the previous year.

In March 2025, the score of this war was a stalemate, a draw. Ukraine had beaten back the Russian advances early on and reclaimed more than 50 per cent of the territory it lost in the early weeks of the invasion. But it had still lost 20 per cent of its country overall, around 10 million of a shrinking population, to death, flight or occupation. Vast swathes of the country have been depopulated. Ukrainian sovereignty has been mostly preserved yet at an utterly awful price. We should note what Ukraine has kept that many countries under these circumstances would not. There is still freedom of expression, and media outlets frequently publish articles criticising the political leadership or military strategy. There is no cult of personality of Zelensky – he appears frequently in the media and fields all types of difficult questions, but I’ve never once seen a poster of him.

The Russians had their international credibility as a military power destroyed. They preserved a land bridge to Crimea for hundreds of thousands of bodies and countless billions of pounds in expenditure, as well as causing a huge capital flight of young and talented people from Russia. The Kremlin had supposedly fought this war to keep Ukraine out of NATO and stop the west from breaching its borders. By December 2024, NATO missiles began flying at Russian logistics targets in Belgorod and Kursk regions. NATO Leopard tanks were patrolling across the fields of Kursk again, in an eerie throwback to the great tank battle of 1943. Any peace deal, if signed, is likely to have NATO members the UK and France providing troops to patrol a premeditated zone. Ukraine really will be an ‘anti-Russia’, armed to the teeth on Russia’s borders. Just like Ukraine’s desire to reorient away from Russia and join NATO, which had been formed after the invasion of Crimea and Donbas in 2014, the Russians had brought this situation entirely upon themselves.

The Russian mobilisation was enough to stem the bleeding and to begin to slowly take more territory from Ukraine. But it was never enough to win the war. Likewise, the West’s impressive-sounding but, in reality, delayed and piecemeal support for Ukraine was enough to keep it in the fight but never sufficient to strike a killing blow. If wars are fundamentally ‘contests of will’, then the Ukrainians wanted it the most, followed by the Russians, followed far behind by the West. Was this the time Europe would finally step up for its own security?

To make this point, one Ukrainian started a crowdfunder for Ukraine to buy a nuclear weapon, raising over $500,000 almost instantly. Some senior figures want to put the missiles back in their silos, ready to fire at anyone who would dare threaten Ukraine again. Oliksiy Honcharenko, a senior Ukrainian parliamentarian, told a panel:

“Ukraine sacrificed its security for the sake of non-proliferation, and everyone can see how that ended up for us. Ukraine’s choice [for] survival is clear. The ideal option is to become a member of NATO and get a nuclear umbrella. If we are not accepted, then I see no other way than restoring our own nuclear capabilities.”

A document from Ukraine’s National Institute for Strategic Studies, which reports to the President’s office, made the case that Ukraine could produce tactical nuclear weapons within months.

In February 2025, I took another trip to the nuclear missile museum. Now, with Ukraine betrayed again, the talk was of resurrecting the sleeping devils here.

“I felt bad when we had to give up our nuclear weapons,” said Valeriy Kuznetsov, a 71-year-old former Soviet officer who spent most of his life working here. “It was a crime by the leaders of the countries that forced us to sign the memorandum, and our own leaders who agreed to do it. For sure, yes, I’d like Ukraine to have nuclear weapons again.”

It is not only Ukraine that is looking at a nuclear deterrent. Soon after Trump cut off aid and intelligence to Ukraine, the Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk announced that his country could no longer rely on US protection. He ordered that all young men must report for compulsory military training and hugely increased investment in his country’s already formidable military.

This will be one of the great repercussions of this war; no country will ever make the same mistake Ukraine did in 1994 and trust international alliances and the rules-based international order to protect them. Only hard force will be a real deterrent. What autocrat – like the Korean Kim family or the Iranian ayatollahs – would give up a nuclear deterrent after looking at the fate of Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan dictator who abandoned his nuclear programme only to be stabbed to death with a bayonet? What British Prime Minister or French President could convince their voters to peacefully eliminate the country’s nuclear weapons programme after seeing the photos of Bucha and Mariupol? This is a brave new world, the implications of which we have not yet come close to grasping.

There is hope in Ukraine, and it lies in the ordinary men and women, Ukrainian and foreign, who have risked or given their lives to fight for the values of the democratic and liberal order, even as those values themselves erode worldwide: Kateryna picking up her dead fiancé’s drone, injured Serhiy’s desire to return to the front line and the mad dash of volunteers and journalists to support survivors and to report on the carnage that remains every day.

Some of the harshest criticism of Trump’s decisions came in fact from family members of his officials, many of whom had served Ukraine in various ways. Nate Vance, cousin of J D Vance, who fought in the Ukrainian armed forces, called Trump and Elon Musk “Putin’s useful idiots”. Then there was Meaghan Mobbs, the daughter of US Special Envoy Keith Kellogg who had been a great disappointment to Ukraine. She gave a speech at the Kyiv War Museum about the folly of her home country’s policy of pushing a peace that was a barely disguised Ukrainian surrender:

“Peace at any cost is not peace – it is surrender, dressed in the false guise of virtue. In many of our societies, we have allowed comfort to become our guiding star and the pursuit of ease our mission … It is a dangerous lie … When we believe there is nothing worth defending, we lose the very essence of what it means to be free.”

It was an extraordinary demonstration that not everyone in America had abandoned its founding ideals.

She continued her grand remonstrance by saying:

“We do not fight merely against what stands before us; we fight for what stands behind us – our families, our homes, our faith, our way of life … We do so not because we are warmongers but because we understand the greatest sacrifice we can make is to die for what we believe.”

In doing so, she became one of the ordinary people who the war in Ukraine had turned into a hero.

War, I said at the start of my book, changes the nature of all those who go through it.

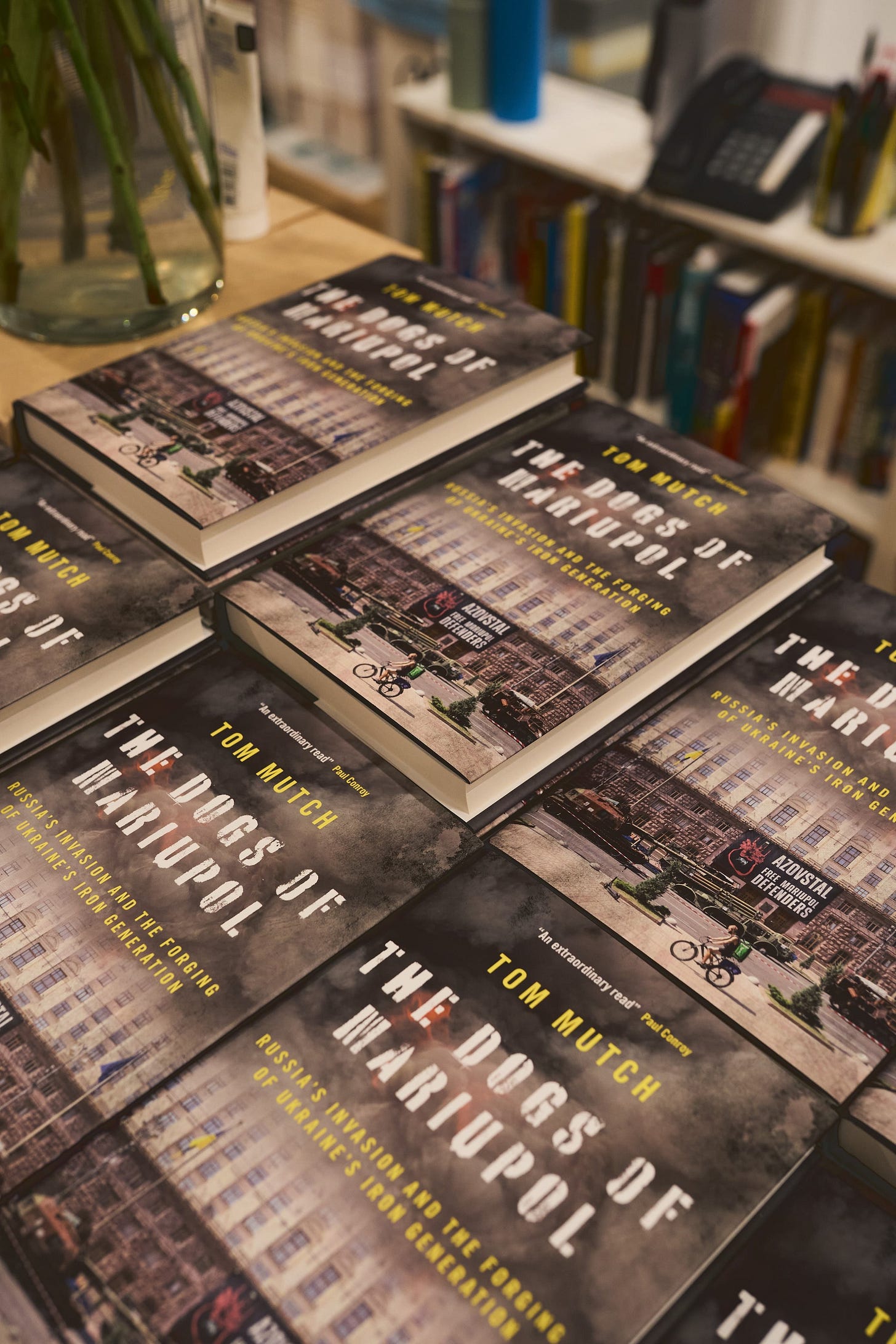

The Dogs of Mariupol: Russia’s Invasion and the Forging of Ukraine’s Iron Generation by Tom Mutch is published by Biteback Publishing and is available here.

He also writes on his own Substack.