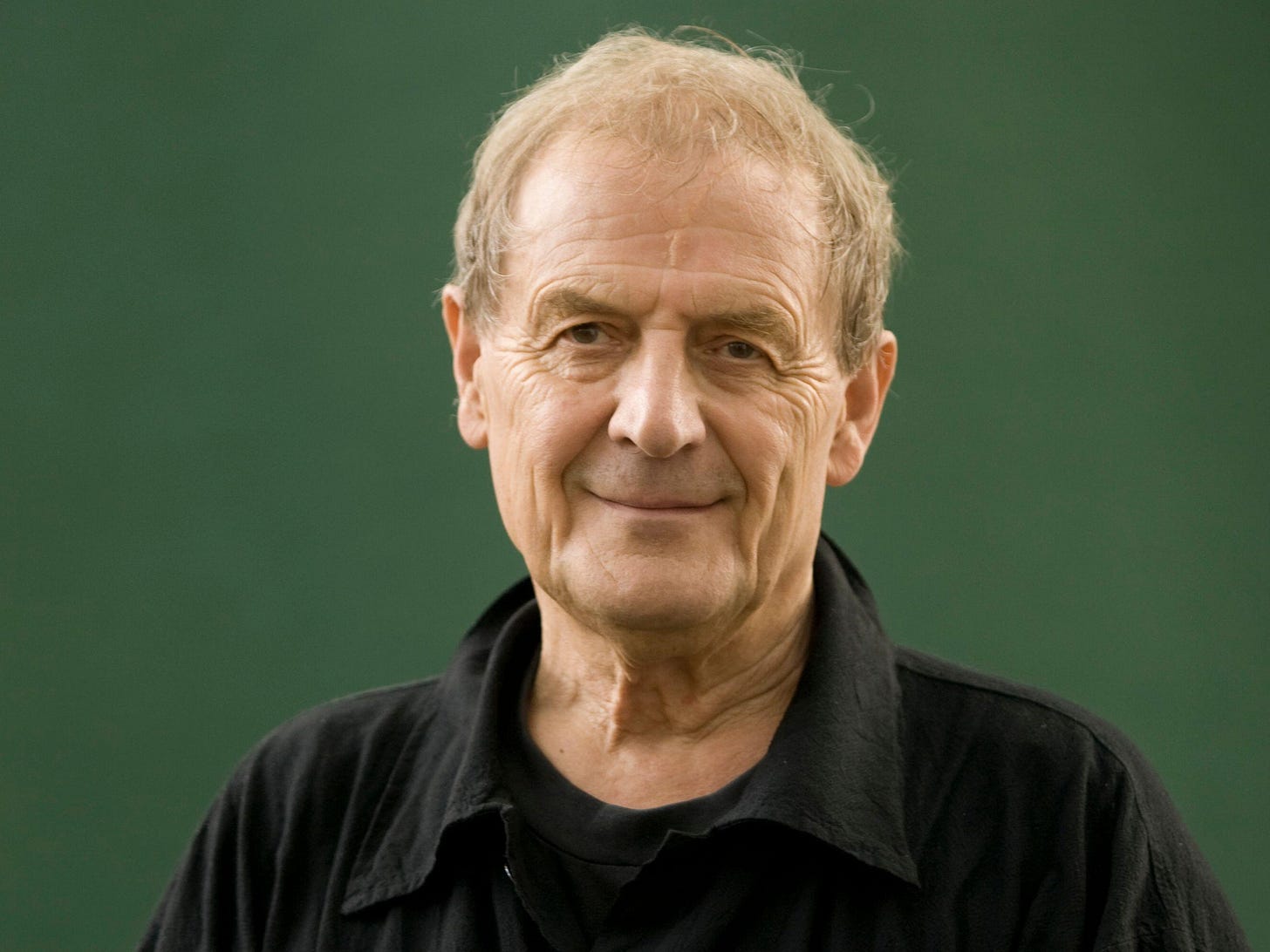

Tony Harrison Remembered by Richard Eyre

Sir Richard Eyre on his long friendship with the late poet, and the blizzard of protest around the film they made together featuring Tony Harrison reading his controversial poem V

Tony used to say, “the beat is in the blood”, in the iambic thumping of the heart, the rhythm of breathing, of walking – the pulse of life. It’s hard to imagine that his beat has been stilled.

He wrote almost invariably in the iambic metre and all his writing is rhythmic, rhymed, memorable, alliterative, dramatic and impenitently English. Its voice is musical, sensual, working-class and Yorkshire – a voice with a sense of place and class, a heartland from which the speaker has been separated. “You should be able to feel the language,” Tony said, “To taste it, to conscript the whole body as well as the mind and the mouth to savour it.”

I first met him in the early 1980s in the National Theatre’s greenroom bar after a performance of The Mysteries, Tony’s brilliant version of the York and Wakefield mystery plays, whose brilliance was matched by Bill Bryden’s direction and Bill Dudley’s designs. The bar was noisy, fetid, fogged with cigarette smoke. Tony, red wine in hand, dressed in faded denim like a French railwayman, stood like a shaman surrounded by acolytes – Brian Glover, Barrie Rutter, Jack Shepherd, Dave Hill – Yorkshiremen all, who he was encouraging to refrain from thumping a recalcitrant unbeliever who had objected to their clamour. “Less noise, more sense,” he said, and the row receded.

“I’ve read your work,” I said to him and quoted a line from The Morning After (August 45): “The fire left to itself might burn for weeks”.

“That’s not quite what I wrote,” said Tony, “it’s ‘smoulder’ not ‘burn for’” and so began our long friendship.

Tony was born in Beeston, the son of a baker, and was educated at Leeds Grammar School and the University of Leeds. The baker’s son from Leeds was probably the most cosmopolitan man I’ve ever known: multi-lingual (Greek, ancient and modern, Latin, Italian, French, Czech and Hausa), much travelled, living, often rather precariously, between London, Florida, New York, and Newcastle. An expert in many cultures, with a curiosity about many others. Fastidiously knowledgeable about food, wine, literature, music, and the theatre. Tender, witty, wry, volatile, living up (or down) to the Yorkshire stereotype only in his rare but formidable stubbornness and intransigence.

His first collection of poems was published in 1970: it was called The Loiners, an old slang name for the people of Leeds. He pursued its themes for the rest of his life – the contrast between his working-class background and the world opened up to him by education. He said: “I wanted to write the poetry that people like my parents would respond to.”

His best known poem is V., published in 1985, set in Holbeck cemetery on the edge of Beeston Hill, which deals with the ‘versuses of life’ – communism v fascism, Left v Right, soul v body, heart v brain, family v freedom, husband v wife – and how to unify them. In 1987 I made a film for Channel 4 of Tony reading his poem, interspersed with documentary images.

Poets who read their work in public can often be maddeningly diffident and awkward. Tony wasn’t of this school; he was a poet who performed rather than read, without self-regard and without self-indulgence and without the spurious ‘performance’ values that actors often bring to the reading of poetry. He didn’t, however, neglect the demands of volume and articulation, the sense of the event, and the awareness of his audience. He was metrically unnervingly constant: when we were filming v. you could have set a metronome at the beginning of the performance and forty minutes later the poet would still have been in sync with it. In addition, he could accommodate with an actor’s instinct instructions about camera movements and eyelines. He could, as we say, ‘take direction’.

When the film’s broadcast was announced there was a blizzard of protest. As ever, popular newspapers found rich resources of moral indignation: “FOUR LETTER TV POEM FURY!” cried the Daily Mail on their front page, which brought to the poem an audience whose size could never have been imagined without their gift of free publicity. It was an audience who largely came to the poem out of curiosity and was surprised to find that not only could they understand it, but they were moved, amused, even educated by it. Tony became the uncrowned poet laureate – a truly public poet – and V. is now a set text in many schools.

I valued Tony as much as a playwright as a poet. Poet and playwright are usually seen as mutually opposed roles – the poet a solitary figure answerable to no one but his own talent and conscience, the playwright a collaborator, colluding in the pragmatism and expediency of production and the approval of the audience. We easily forget that our dramatic tradition is founded on verse drama, that our national playwright was a poet.

Most of Tony’s work for the theatre was adapted from other languages – The Misanthrope from Moliere, The Prince’s Play from Hugo, Phaedra from Racine; The Oresteia, The Trackers of Oxyrynchus, based on fragments of a lost play by Sophocles, and The Mysteries, of course, from Middle English. They’re all mediated in Tony’s own voice between a foreign language and English verse, between one culture and another, between the past and the present. And if you look at photographs of twelve Yorkshiremen in clogs dressed as satyrs with long tails, pantomime-horse ears and magnificently gross erect cocks in Trackers, it’s hard to think there was a bolder playwright working in this country in the late 20th Century.

I don’t know if despair was his constant companion; melancholy certainly was. More than once I heard him say that if it weren’t for his ability to write he would go mad, that writing was a way of expressing, of reducing, of controlling, thoughts and feelings that would otherwise spray into chaos. It was, appropriately, the author of The Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton, who said in the 17th Century that all poets are mad. Perhaps without their poetry they would be. But this is to shadow Tony’s capacity for love and friendship and if there’s anyone who could testify to that it’s Siân Thomas, his partner for 35 years. This is the last stanza of Tony’s poem about his mother:

I believe life ends with death, and that is all.

You haven’t both gone shopping; just the same,

in my new black leather phone book there’s your name

and the disconnected number I still call.

There are so many of us who won’t stop calling.