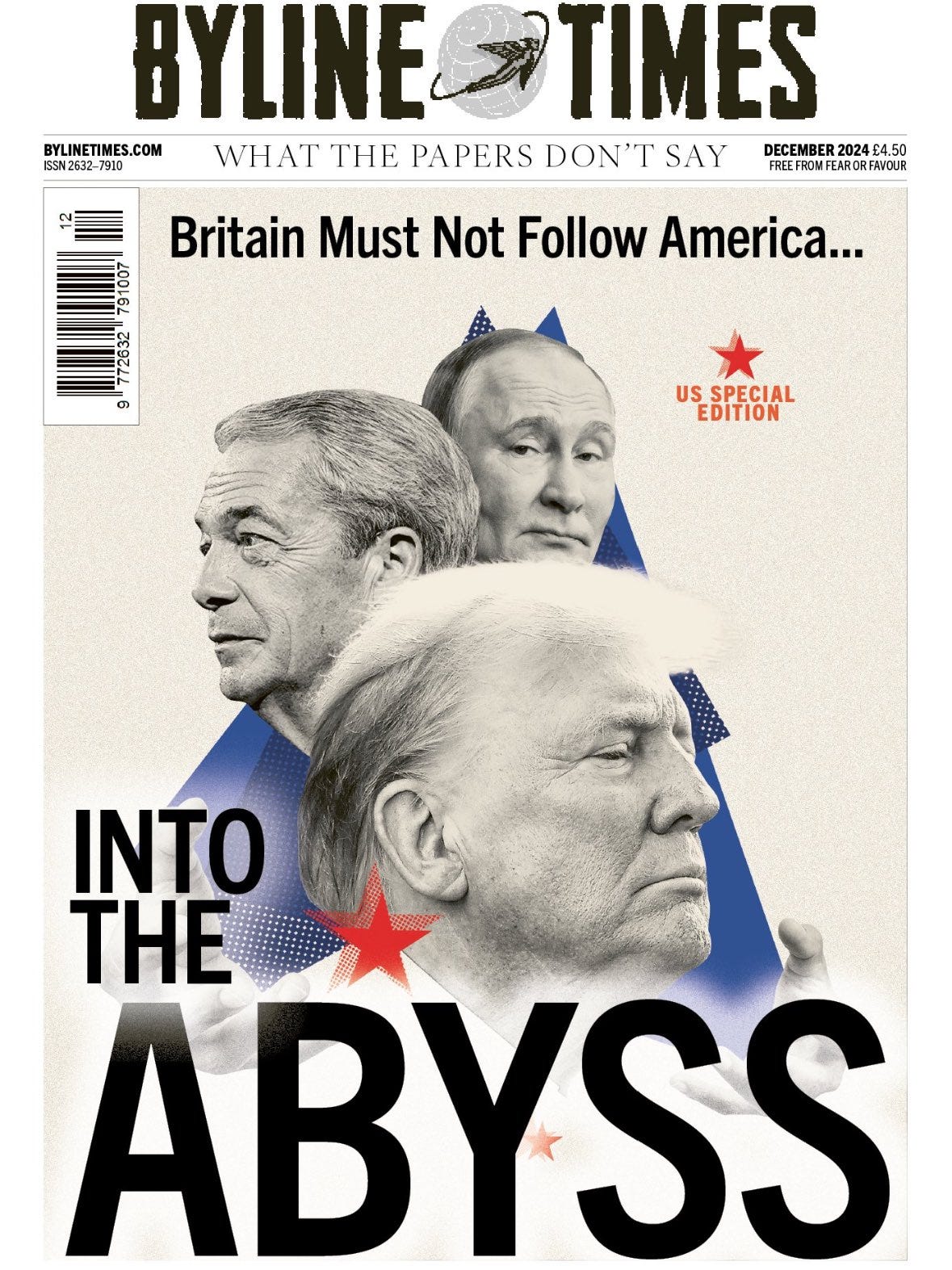

The Psycho-Social-Techno Politics of ‘MAGA’ Trumps Democracy – And The Liberal Left Needs an Answer

Donald Trump’s second victory in the United States is a warning sign to democracies everywhere of the centrality of emotions – and their manipulation – in our politics

The following article is an exclusive free preview taken from the upcoming print edition of Byline Times. Subscribe to be among the first to get your copy

Driving Towards Donald Trump

A year before the American election, I sat down in a succession of New York City taxis. The story was always the same. The drivers didn’t much like Donald Trump, and weren’t always comfortable with his approach. But they were all leaning towards voting for him against Joe Biden.

“He’s a businessman,” one said. Another: “I may not agree with him but he knows how to get things done.” One middle-class Punjabi Uber driver, who lived in a well-to-do community in Long Island, said he and his neighbours would all be opting for the Republican candidate.

The one exception, a Greek New Yorker – who shared how devastating it was that he had never seen his country’s Parthenon Marbles in Athens because he has never been to London (where they sit in our national museum as the Elgin Marbles) – tried to explain the phenomenon: “The thing about Trump is that he’s not a politician.”

When Trump was re-elected to a second term as President on 5 November, I was shocked but ultimately not surprised. I thought back to those cab drivers who made their living in one of the most liberal parts of the United States (where the Democrat vote share fell from 76% in 2020 to 68% this year).

They felt the city had deteriorated, that their material lives were in decline. More than that, though, I recalled how ordinary they all were. No MAGA hats or Trump rallies for these men. They were but a miniscule of a tiny sample of how life in America was no longer turning out the way they expected it to, and it bothered them. So much so that not even the prospect of Trump’s eventual criminal conviction seemed to matter.

The only candidate in this year’s race who was speaking to them was the millionaire reality TV real estate entrepreneur born with a silver spoon in his mouth. And the Democrats seemed to have no idea.

Politics Isn’t About Politics

Trump’s triumph puts beyond doubt that the events of 2016 – the US Presidential Election of that year (and, to a significant enough degree, the vote for Brexit in Britain) – were ‘freak’ events momentarily disrupting politics as we know it.

We don’t know politics. Not anymore.

The notion that it is fought and won, if it ever strictly was, on how the everyday lives of people can be improved through practical policies and traditional ideology is over.

In this new era, pragmatism is viewed primarily through the prism of emotionality, with more visceral instincts amplified by populist politicians capitalising on the deep anger born of gross inequality, and tech disinformation feeding the polarisation and the need for a sense of ‘psychic justice’.

Until progressives are willing to understand and confront this – that the lens through which they view what politics is for and about, and how and where they form such ideas, is significantly different to how others, particularly those they disagree with, do – these ‘shocks’ will continue. Because politics isn’t about politics anymore.

That significant numbers instead see it as a vehicle to channel their fears and resentment-driven emotional instincts – beyond facts – is the existential challenge facing democracy today.

The right, both in America and in the UK and across Europe, understands this. Well.

If those of more progressive politics cannot produce a response – which factors in this uncomfortable reality: that they must engage with the world as they find it, not as they hope it to be – democratic politics will continue to be left vulnerable to the kind of far-right oligarchical forces now gathering around the entire United States Government.

We’re not funded by a billionaire oligarch or an offshore hedge-fund. We rely on our readers to fund our journalism. If you like what we do, please subscribe.

As the UK-based American author, Brian Klaas, Associate Professor in Global Politics at University College London, told me in May: “My biggest insight into politics, which I got from working in political campaigning before I became a political scientist, is that the overwhelming majority of people do not think about policy at all. And this is something that people who work in politics, and especially on the political liberal left, have just completely missed.”

Beyond a hardcore group of Trump supporters who were never going to switch allegiance, much of the analysis of the scale of Kamala Harris’ defeat has focused on ‘the price of gas’ factor – that the economy (stupid) was the reason that fuelled so many Trump voters and that he alone offered any recognition of the reality of inflation felt by these people. Meanwhile, Harris spoke of needing to ‘save’ a system of democracy many people felt had utterly let them down.

But what Trump has also long understood is how people feel and experience their realities is key. This was an important feature of his 2016 run, when Cambridge Analytica-led psychological data profiling was illegally used on millions of Facebook profiles – a covert strand of an ‘information war’ long strategised, not only by GOP figures, but further afield, Vladimir Putin.

While the 2024 US election was, then, about the economic reality of Biden-Harris’ America, it was also about Trump being the natural home for people’s more primal projections of this perceived justified grievance.

It’s not either/or. Policy has a place, but equally – if not more – important is how people see the world around them, who they blame for this, and what compensation is forthcoming. This, by its very nature, takes us into both a psychological and emotional realm. Because people are psychological and emotional beings.

The notion of people voting for Trump ‘to tear down the system’ is inherently emotional and psychological and is connected, on a factual level, to the evidence that the system doesn’t work for them and hasn’t for many years. It’s an interaction of instincts.

It’s about the economy and the cruelty that compensates.

It’s about gross inequality and the need to make America great again.

It’s about the US not getting too tangled in global affairs and the need for a hyper-masculine ‘strongman’ to confirm the US as a beacon of patriarchy and evangelicalism.

It’s about the fact that secure work used to provide a sense of identity to many and that those unmoored identities are now being channelled into new vessels of self-esteem creation because that secure work no longer exists.

Visceral Instincts

For Klaas, Britain “lags behind the Trump effect by several years, but there are aspects of it seeping in from the US”. Back in May, he was speaking of why the Conservative Governments in Britain were using issues such as the Rwanda policy as part of a politics of ‘performative cruelty’ borrowed from Trump.

“Trump wasn’t trying to pretend that he was doing cruel things for good reasons – he was just trying to punish people who, to those on the political right, deserved punishment… you can do a heck of a lot of damage in a really vindictive, petty, cruel way, and actually consolidate support among a certain percentage of the electorate,” he observed.

But there are lessons from Trump’s politics even for a Government of the left not engaging in such tactics in the UK.

While a base of supporters is in favour of cruelty for its own sake, policies are important for others. But, in both cases, an emotionally-resonant ‘big vision’ of how politics can change people’s lives or their country takes primacy. People want something to believe in. And, in Trump, enough American voters felt that he was back fighting for them, despite all of the establishment’s attempts to ‘persecute’ him.

“Why this is so culturally resonant… is that a lot of politics for people who don’t think about it every day equates to distributing justice and giving people what they think they deserve,” Klaas said. “This idea that ‘these people’ broke the rules and they deserve to be punished… that impulse is very old. When we look at politics, it’s about arguing about your policies – but you’re not going to convince these people by saying ‘here’s our new policy idea’.

“On immigration, this speaks to the question: what does it mean to be me? It’s an identity question. People usually talk about ‘identity politics’ as some abstract or policy-driven issue – but I think a lot of people feel it internally. In the UK, this is the concept of some people feeling immigration is changing what it means to be British. And identity is very, very important to our sense of self.

“But when you argue about that using a statistic, it’s really ineffective – because that’s not the level at which these people are thinking about this problem.”

In 2019, many readers found my exploration of why my parents – immigrants to Britain from former countries of the Empire – had voted for Brexit genuinely illuminating. The presumption was that people from these minority communities could never have voted ‘against their own interests’ in this way. But that’s not how they viewed the EU Referendum. And that’s not how the complexity of identities works.

A mixture of them feeling a deep sense of loyalty to Britain as people who no longer saw themselves as ‘immigrants’ and so disliking the perceived benefits given to European immigrants, as well as a feeling that the Empire had exploited countries such as India and treated them like second-class citizens and therefore Britain’s loyalty should, in return, lie with them, not immigrants from the EU, were all part of the mix. These reasons were historical, personal, emotional, irrational, philosophical, unconscious, prejudiced, uninformed, and logical. None of them were touched by the remain campaign’s emphasis on rational argument and caution.

A few years later, I recalled my parents’ story to a Labour MP, commenting that increasing numbers of immigrants were now voting for the Conservatives. Their response was to suggest that this is why Labour needed to keep showing that it was “pro-migrant”. It missed the point completely.

We need your support to build an alternative to the Oligarch-owned media. Help us find another subscriber by giving your friends and family the gift of a subscription

Tech Changes Everything

Emotionality and psychology have always been central to politics. Political communication has often been predicated on the feelings aroused in voters, rather than just the putting across of policies.

But, as inequality has increased to record levels in both the US and the UK, many more people have been primed to look for alternatives to the system, questioning it all (as they rightly should) because it doesn’t help them with achieving basic fulfilment in their lives: a viable income, social mobility, community and purpose – the external drivers that feed our internal sense of ourselves.

Our esteem, our regard, our dignity, can too easily degenerate into our self-hate, our lack of care, our shame. Many now feel like outsiders in their own lives.

In this context, and with social media creating both more alienation and a sense of ‘being part of something bigger’, feelings of hurt and hate are encouraged and amplified – beyond anything we have seen play out in the ‘traditional politics’ of old. People can now be personally and directly targeted with messages, wherever they are and at any time, indefinitely, giving emotional charge to the issues they already feel bad about.

The tech revolution has changed everything.

For many outside of progressive, liberal, and left-leaning circles, social media platforms rife with conspiracy, disinformation, and hate are what people are seeing daily – and where they develop their sense of the world they live in. Social media is now the media.

In this ecosystem, what matters is what resonates, regardless of how outrageous, and getting riled up is rewarded by the algorithm. Again, there is the interaction of such visceral instincts with the more factual grievance of the system not working in their interests.

Haitian immigrants eating people’s pets in Springfield, Ohio, seems a little wild – but the underlying point that illegal immigration still appears to not be under control is not. Whether immigration is the real reason for people’s woes is another issue still.

But conspiracy is only conspiracy because someone is trying to cover up the truth.

That those on the liberal left have failed to grasp how utterly tech has changed everything in our politics and culture – especially given revelations back in 2017 of the role of psychological profiling through social media – is exploited by the right, which has quietly been writing the rule book on this new ‘Wild West’ for years. Trump funder and now advisor, X owner Elon Musk, is simply the most logical next step in this trajectory.

Even Barron Trump, the youngest child of the President-Elect, brought something to the table in this election for his dad, encouraging Trump to do the rounds of cult podcasts with millions and millions of listeners between them, with Joe Rogan being one notable endorsement resulting from this strategy.

Combined with the familiar fact-free takes of Fox News, and the world’s richest man using his social media platform X (formerly Twitter) to campaign openly for Trump, this hard-right-leaning, conspiracist, hyper-masculine, opinion-driven ecosystem had a huge role to play in his re-election. Over three hours on Rogan’s show, Trump gave millions of listeners an insight into who he is. Harris’ strong television debate performance was long forgotten, if not watched at all by Rogan’s followers.

Forget the likes of The New York Times’ editorial board opinions or The Washington Post’s lack of endorsement for Kamala Harris, this new ecosystem is now embedded in how the new politics works, particularly in the United States.

And the left is left reeling.

Vision Not Vibes

Another criminally-convicted ‘anti-establishment’ figure who understands the power of this new political-media ecosystem is the far-right English Defence League founder Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (known as ‘Tommy Robinson’).

Before being sent to prison for contempt of court in late October, and in response to my colleague Josiah Mortimer, he posted on social media that Byline Times’ Chief Reporter was a “fake news wanker” and “write whatever you want, no one gives a f**k any more. We are the media.” Those last four words were telling.

When Yaxley-Lennon, who was widely credited with helping to fuel this summer’s race-driven riots across the country, says ‘we are the media’, he is providing an insight worth dissecting. Succinctly, he summarises how ‘mainstream media’ is no longer ‘mainstream’. Disenchanted, and feeling disenfranchised, more and more people are looking for alternative mediums through which to make sense of their worlds.

This should be at the top of Keir Starmer’s concerns when considering how the next four years of his tenure will play out.

While the UK and the United States are very different countries, with very different cultures, Trump’s victory fires a warning shot for the left across the Atlantic.

One of the biggest lessons from his triumph appears to be that competence and delivery is not in itself enough. Although Joe Biden restored the US economy to growth, the rising prices of groceries and other amenities meant not enough people experienced this in their daily lives. Trump was also deft at not avoiding the truth: that many Americans feel that the neoliberal economic order, which has led to vast inequalities across society, has failed them.

Unlike Bernie Sanders in his 2020 presidential candidate bid and since, this wasn’t a reality Kamala Harris was willing to confront: that enough Americans believe the system has failed – and so offering more of the same to save democracy with joyous vibes wouldn’t go down well.

Her freedom had a very different meaning from the freedom desired by MAGA supporters. Both are advanced in the name of American patriotism. Shared realities no longer exist.

In Britain, Starmer’s Labour Party was elected in a landslide election in July following years of incompetence, corruption, and scandal at the hands of the Conservatives. With public services at breaking point, and a cost of living crisis made worse even for the middle classes through barely-there Prime Minister Liz Truss’ disastrously libertarian mini-budget, Starmer vowed to restore trust in politics by delivering a ‘government of service’.

And yet, events in the US indicate that mere delivery may not be enough if people don’t see the change in their everyday lives and understand what bigger vision Starmer has for the country.

For all the talk of the need to rebuild, neither the words ‘poverty’ nor ‘inequality’ were mentioned in the statement accompanying the Government’s recent Budget, even though some of its measures aim to alleviate both. The silence is curious. There was also little framing of the tax rises announced in terms of boosting funding for the NHS. ‘Doom and gloom’ has been the prevailing media narrative since Labour took office.

With an established press still holding considerable influence over Britain’s politicians (if not the public), in contrast to America, Starmer’s approach seems too predicated on preventing a media backlash and too little focused on conveying simple but impactful messages that resonate with people – rather than just abstract concepts they have heard uttered many times, such as ‘growth’.

Meanwhile, the right’s media dominance through its ecosystem of traditional newspapers, new social media platforms, the likes of GB News, and more covert Facebook groups is ready and waiting. With no sign that Starmer is interested in press reform, the danger is he is held captive by the very forces he is trying to appease – until the time comes when they decide to hang him out to dry.

As this trap is laid, transatlantic connections, ideology, and funding are flowing across the Atlantic, with Byline Times recently revealing the millions being poured by those who funded Trump’s most recent presidential run into London’s Tufton Street network of opaque think tanks.

The election of Kemi Badenoch as the new Conservative Leader, who this year defended the controversial commentator and writer Douglas Murray, is another sign of how one of Europe’s most traditionally successful parties has been taken over by more concerning tendencies – a move towards what the Conservative writer Peter Oborne has labelled the “far-right”.

Then there is Nigel Farage and his Reform Party, which now has five MPs in Parliament. He attended a number of Trump rallies this year and predicted that his friend would win a second time around. An investigation by Byline Times as this summer’s riots were unfolding uncovered a number of Reform supporters’ Facebook groups, many of which were full of far-right views, with some discussing the ‘optics’ of keeping their distance from ‘Tommy Robinson’, despite the synergy between Reform and Yaxley-Lennon.

In July’s General Election, Reform came second in 98 constituencies, 89 of these to Labour.

Long Shadows

By not confronting the complexities of how questions of politics are now intimately connected in new ways with people’s emotionality and psychological drives – as Farage understands, and put to stunning use during the Brexit campaign – the Labour Government leaves Britain open to the risk of such dark forces emerging through the ballot box in our own country.

When enough people feel invisible, and like their lives have not tangibly improved but are getting worse, more radical alternatives begin to look appealing.

Accepting the psycho-social-techno dynamics of Trump’s success doesn’t mean endorsing his politics or giving credence to people’s reasons for voting for him – but the liberal left must confront why it is appealing, and not dismiss its resonance as mere exception, stupidity, or madness.

This necessarily involves engaging with why personality, chaos, cruelty, grievance, stability, disruption, strength, big and simple messages giving people hope seem to matter.

How the liberal left embraces such lessons, without compromising its own integrity or values, is a conundrum without an immediate solution. But one is urgently required.

Because the deeper, more disturbing, truth is that psychic victories matter when they are the only victories there are.

Trump’s border wall with Mexico never needed to be built, because he has constructed a far more sturdy wall in the mind of his supporters, which lives within them, giving them a sense of recognition they have for so long gone without.

Psychotherapist Carl Jung observed that “the best political, social, and spiritual work we can do is to withdraw the projection of our shadow onto others”. Trump is the Shadow Man.

How do you catch a shadow?

Hardeep Matharu is the Editor-in-Chief of Byline Times

We need your support to build an alternative to the Oligarch-owned media. Help us find another subscriber by giving your friends and family the gift of a subscription

So called “progressives” do get it, in the main. But it’s the politicians who don’t get it and very very few of them could be called “progressives”, and certainly none in leadership positions. Labour has cleansed them, while Tories are anti-progressive. There’s plenty of bloggers and other commentators who get it but they don’t want to be politicians and who can blame them, but that is the problem. Politics is so toxic, so authoritarian and so captured that you need to sell your soul to join that club.