Shamima Begum: How Politicians and the Media Ignore the British Roots of Radicalisation

A new BBC documentary exploring the story of the schoolgirl who left London to join ISIS only scrapes the surface of the biggest question of all: why she did it, writes Hardeep Matharu

“In a way I felt kind of relieved” was Shamima Begum’s response to seeing Britain for what she thought was the last time. It was 2015 and she was on her way to join ISIS in Syria. Why? I asked out loud to the TV. As a viewer – and journalist – watching this month’s BBC documentary, The Shamima Begum Story, on how the now 23-year-old left Bethnal Green aged 15 to join the infamous terrorist group, I wondered why she had felt relieved. It’s a question she wasn’t asked.

Begum’s is a story that continues to fascinate and enrage, with little desire for nuance. For some, she knew exactly what she was doing when she left east London to join the organisation that had beheaded UK and US citizens in live broadcasts streamed around the world. For others, she was a victim of grooming and child trafficking who has paid the price with the revoking of her British citizenship.

In the many media reports about Begum, we are told she lacks empathy. How her three children are dead. Her husband was an Isis fighter. And she said she saw severed heads in bins. That she is a narcissist adopting Western clothing in a bid to rehabilitate her image. But, there is very little about why she actually left Britain to join ISIS.

This new documentary, and an accompanying podcast by BBC Sounds, attempts to explore some of the complexities, and does a fair job. But it too fails to properly interrogate the questions there are no easy answers to. The issues, not excuses, worthy of excavation but that point to no simple solutions.

How does a person from a minority background deal with growing up with conflicting identities and a feeling they don’t belong anywhere? Why do structural inequalities and racism cause the alienation and practical challenges they do? How, as a society, can we be culturally dynamic when difference is always hard?

Over just six-and-a-half minutes – of a 90-minute documentary – Begum is asked what led her to join ISIS.

“I didn’t feel British or Bengali,” she tells director Joshua Baker. “I didn’t feel Bengali because I didn’t want to be Bengali. And I didn’t feel British because I feel like I wasn’t able to be British even though I wanted to be... You want to be accepted by society but I didn’t feel like I was accepted by society either. Because of racism and other things.”

The “racism and other things” deserve further questioning but are left unexplored.

A small segment briefly describes Tower Hamlets, the borough in which Bethnal Green is situated and the area with the worst child poverty rates in the UK, where Bengali and English are the two most commonly spoken languages and the financial centre of the City looks down in the near distance. It’s a place where people like Begum can grow up with a conflicted sense of identity, the documentary suggests.

“It’s really hard wanting to integrate into society but your family holding you back because their idea of being British is being loose and like immoral,” she says. “That’s not what I wanted to be obviously, I just wanted to be a bit more free.”

She was “depressed and quiet and obedient” around her parents and “just not content with my life and in a way resentful to my family”. While many teenagers feel this way, Begum describes it as being “oppressed”.

The difficulty of managing your family’s cultural expectations in a culture with different expectations – regardless of your own expectations – is not explored any further with her (although as a female journalist from an immigrant background it would have been a key area I would have delved deeper into, given how real I know such inner conflicts to be – I live them). Even so, many people from a similar background, and with similar inner conflicts, do not leave the country to join a terrorist group. What was different here?

Begum explains how her friend Sharmeena Begum fled to ISIS first. Both girls became religious around the same time – although the paradox of not feeling, or wanting to be, Bengali and then following Islam more religiously is barely touched on. How does one lead to another? This viewer was left wondering.

Her friend told Begum “how we had an obligation to go” and how “you won’t be able to practice your religion properly in the UK… the UK is racist and it’s Islamophobic… why would you stay in a place that doesn’t even want you?” Again, Begum is not asked to elaborate on what the racism and Islamophobia in Britain her friend was using as reason to leave it to join a terrorist group entailed.

The brief focus the documentary gave to some of these bigger questions was certainly thought-provoking, but could have gone much further.

Shiraz Maher, director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, explained how “ISIS propaganda is well known for the ultraviolence but only about 8 or 9% of ISIS’ output was that ultraviolence”. He continued: “Of course, that’s the bit that captures the headlines and therefore it’s what we all know and associate with the movement but that’s not the only part of the picture that she will have been offered… [ISIS also communicated that] this is where your sense of identity and belonging have their natural home and this is where all these issues are resolved.”

What did Begum herself believe she would find in Syria? “This utopia that was created for me as someone who didn’t know who she was at the time and who wanted an identity and who wanted to feel accepted by a community which I did not feel back in the country,” she says on the accompanying podcast I’m Not a Monster: The Shamima Begum Story. The subject is left there.

But the established media, and right-wing commentariat, have seldom helped to create the conditions in which any deeper, more complicated, discussion of Begum’s story can take place.

She was there for the media to “obsess over”, she says in the documentary, and to “continue the story”.

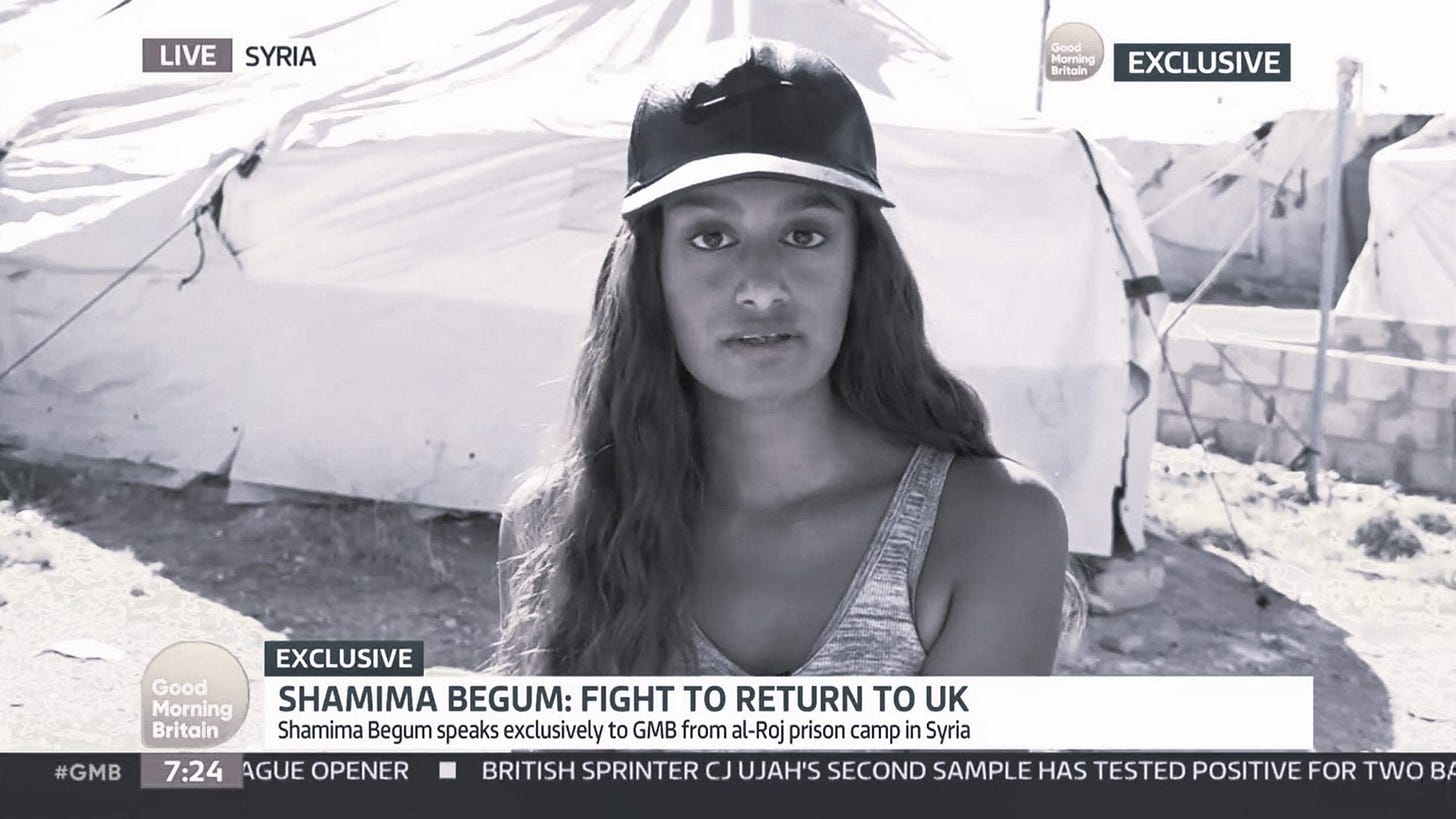

Shortly after being found in a refugee camp in 2019, and having just given birth to her third child, journalists knocked on the door of the delivery room. “I felt very used by the journalists, like they did not care about my mental health and where my mind was at that time,” she says.

One segment of the documentary shows ITV footage, in which a reporter sits down with Begum – holding her newborn – for a broadcast, asking if she had any news about her case. When she said she didn’t, he hands her a copy of a letter sent by the UK Government to her parents stripping her of her British citizenship. She reads it aloud on camera; the shot zooming in on the typeface. “What do you think?” the reporter asks. When Begum says she feels it’s a bit unfair on her and her son, the journalist tells her: “But you’ve done this to your son. This is a consequence of your actions.”

An unwillingness to explore the implications for Britain’s politics and society of Shamima Begum’s story isn’t just seen in the media – it appears to be the policy actively being pursued by politicians.

A review of the controversial counter-extremism strategy Prevent, published this month, confirmed the need for “placing greater emphasis on tackling ideology and its radicalising effects, rather than attempting to go beyond its remit to address broader societal issues”.

Despite the rising numbers of far-right attacks in recent years, the review found that “Islamist terrorism is severely under-represented in Prevent” and that there has been an “institutional hesitancy to deal with Islamist extremism” – despite widespread criticism of the strategy’s focus on Muslims and the problematic and ineffective nature of this.

While “broader societal issues”, including identity and belonging, seem too abstract as concepts to do anything about, a number of practical realities feed into them – such as wealth, class, education, opportunity, health, and the disparities in outcomes in these areas. But these are deep-seated, structural problems that go beyond any one strategy.

In her book The Enemy Within: A Tale of Muslim Britain, Conservative peer Baroness Sayeeda Warsi observes “we are aware of the series of issues that are the drivers of radicalisation, so why do we pick and choose only one – ideology – to focus on, speak about, invest in and tackle? Why is ideology more important than inequality, poverty, gang culture, Islamophobia, mental health?”

She writes that, for politicians, “it’s easier to sell ‘it’s their problem’ rather than ‘it’s our problem’” because focusing on Islamist ideology “as opposed to statistics on discrimination, social mobility, criminality, mental health and the legality and success or our foreign policy positions is much easier”.

Warsi makes clear the importance of identity: “The challenge all countries face in an interconnected, globalised world, where our citizens all carry multiple identities, is how do these ‘connections’, this ‘brotherhood’ and multiple bonds of ‘loyalty’ play out in the face of conflict between our very many identities? For me, it’s simple: people pick a side that they believe they have a stronger connection to, and this isn’t necessarily the side they actually have the strongest connection to.”

There are no easy answers to how these issues can, or should, be tackled. They are always complex. But sidestepping Britain’s own shortcomings will get us no further in understanding why people like Begum do what she did.

The reality is that Shamima Begum was radicalised in Britain. Her story is not an experience, the explanation and understanding of which, sits outside Britain. It’s as much to do with the country in which she was born and brought up as it is to do with a horrific terrorist group.

Sitting in an ISIS detention camp in Syria, while politicians and the media continue to feed off of her shock factor, Shamima Begum may be out of sight – but out of mind? As she told the reporter who found her in the refugee camp, she’s “a sister from London” and “a Bethnal Green girl”.

‘The Shamima Begum Story’ is available to watch on BBC iPlayer

Wow Hardeep! This is so important. Sending to Dr. Mia Bloom now.

" The question was never asked "

Much like DAGs "the case of the missing witness statement"

What's omitted is where truth lies.

Excellent stuff.