Shadowman: A Unique Insight into an Epic Scandal

How could anyone hack the phone of an abducted teenage girl? Brian Cathcart reviews Glenn Mulcaire's memoir of the scandal the established press won't talk about

The scale and reach of what we call the phone-hacking scandal is easily missed. It may be nearly 20 years since it first hit the headlines but right now, in the United States, it is chipping away at the credibility of the publisher of the Washington Post, Will Lewis, who is accused of (and denies) helping cover up of hacking in the Murdoch empire.

Here in the UK, the current editors of the Times, the Sunday Times, the Sun and the Mail on Sunday all now stand accused of (and also deny) involvement in unlawful information gathering, while a host of senior executives, newspaper lawyers and former editors have been formally identified by judges as involved in or knowing of hacking and other malpractice.

The Murdoch corporation is reported to have spent more than £1bn settling lawsuits and the Mirror organisation perhaps half that, while the juggernaut of litigation is now heading for the Mail newspapers, accused of (and denying) lawbreaking by Elton John, Baroness Doreen Lawrence, Sir Simon Hughes, Prince Harry and others.

The phone hacking story is no more over than the Post Office scandal is. Like that terrible tale of persecuted sub-postmasters, it is a slowly erupting volcano of delayed accountability, and somewhere near the heart of the action, to this day, is Glenn Mulcaire.

You might remember the name. It first surfaced in 2007, when he was convicted as the techie sidekick of Clive Goodman, the ‘one rogue reporter’ caught hacking royalty for the News of the World, but Mulcaire became a national hate figure in 2011 when it was revealed that he had been part of the Murdoch team who hacked the voicemails of the murdered teenager Milly Dowler.

Today he is on the other side. Hundreds of victims of hacking who have sued national newspapers have benefited from his testimony, confirming that yes, he hacked their voicemails or stole their personal data on instruction from a national newspaper. Or else they have relied on records he kept at the time, later seized by police. As accountability creeps up on these corporations, he is playing an important role.

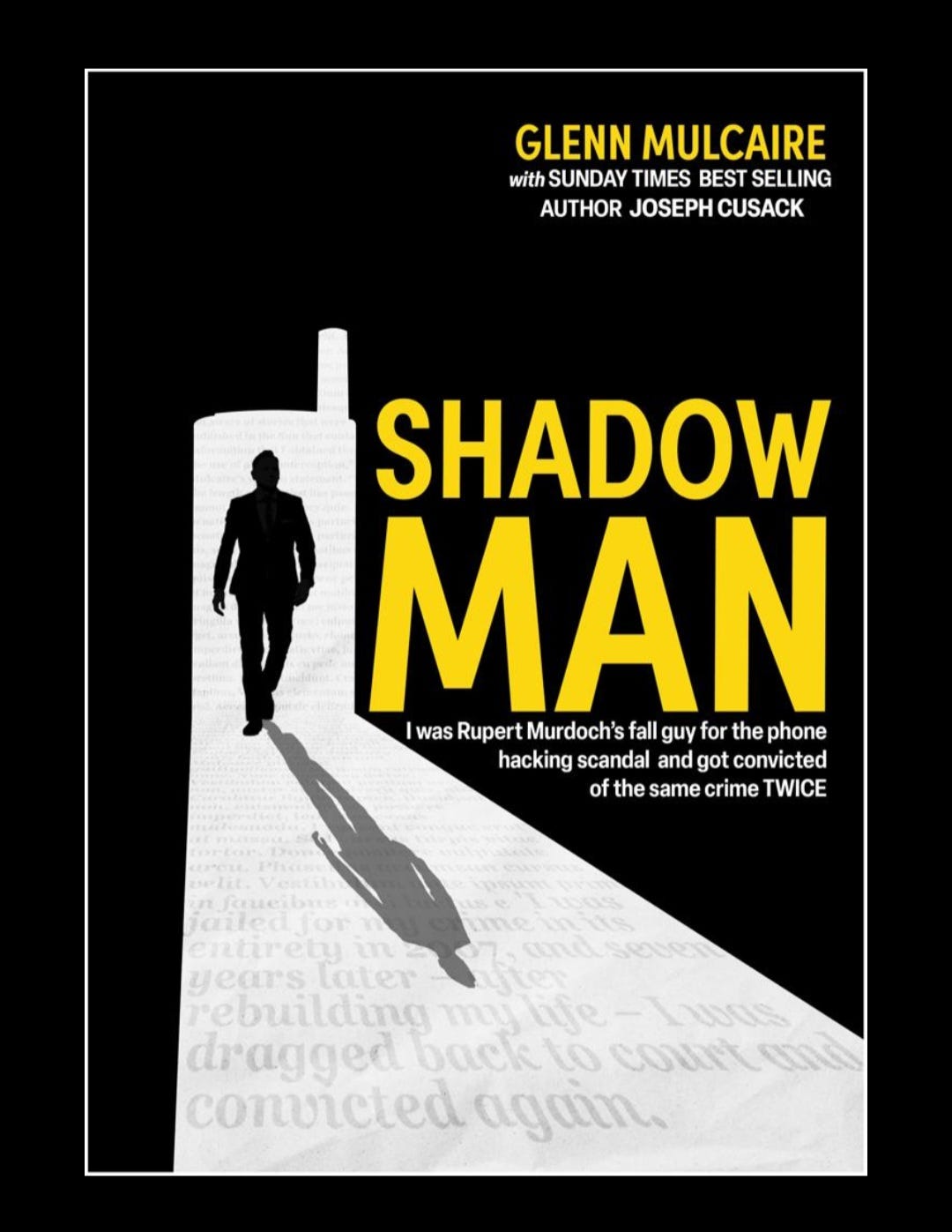

Now he has written his story, entitled Shadowman and just published by Yellow Press. It is a fascinating if occasionally bewildering tale which, if it doesn’t quite present an apology for years of rapacious intrusion, at least offers explanations.

A working-class boy from a central London housing estate, Mulcaire fell into the world of commercial intelligence gathering before he was 20 and discovered a talent for exploiting the new possibilities of the internet. At first the requests from newspapers were just a fraction of his activity, but eventually he was working full-time for the News of the World.

As he tells it, it all made perfect sense. Why would a newspaper, even one as rich as the News of the World, bother to send reporters and photographers to loiter outside people’s homes, offices, or hotel rooms in the hope of catching them off guard, when young Glenn could supply everything needed for an exposé inside an hour without leaving his “Bat Cave” office in a nondescript commercial unit in Surrey.

Call Glenn with nothing more than a name and quick as lightning he would assemble a spreadsheet of personal and financial data revealing movements, habits and friendships, together with numbers for reporters to hack or, if preferred, transcripts of voicemails already accessed. And the target would have no idea.

No surprise, then, that he was soon working almost every waking hour for the paper, probing away from morning until night, neglecting his wife, his family, and his health – or that he was paid more than £100,000 a year for doing it. This was a conveyor belt of scoops, from big ones about David Beckham and the Bulger killers to hum-drum tittle-tattle about soap actors.

(And incidentally, while the paper won award after award for these stories, its editor at this time, Rebekah Brooks, has testified that she had no idea where they were coming from. She is still CEO of the Murdoch organisation in the UK.)

It was like crack cocaine for everyone involved, so easy and so rewarding it was irresistible, and the moral justifications were no better than afterthoughts. Though Mulcaire insists that he hardly ever saw the end-product because he rarely bought a newspaper, he clearly bought into the tabloid mentality that pronounced everyone who was famous to be vain, spoiled, undeserving, corrupt, and thus fair game. By the same logic, crime stories were always crusades for justice, even when – as in the Dowler case – the hackers actually got in the way.

Crook or celeb, the most important thing – and we recognise this because it is invariably passed on to the readers – is to hate and despise the target. And it is clear from what Mulcaire writes that the logic has left its mark.

But there were other people for him to hate and despise too, and they were the newspaper people employing him, who emerge from his narrative as almost uniformly untrustworthy and repellent. And here he provides a twist to the story of the Milly Dowler hack.

His account of what happened in March 2002 is that he was set up by the News of the World. They hacked her phone first, he says, and then commissioned him to do it again to cover their tracks so that if the hack was ever discovered he would get the blame. Which is what happened – a decade later.

It’s not a tale that gets Mulcaire off the hook, but it fits into a wider picture he paints of the newspaper as a criminal organisation of which he too was a victim. And it did not stop at the News of the World because, with his faith in one employer on the wane, he spread himself around Fleet Street, supplying services to the Sun and to Mirror and Mail papers.

His arrests and his two convictions in 2007 and 2014 have left him angry, and it is easy to see why. When these crises came, as he tells it, the Murdoch organisation was happy to dump on the man who had once been its scoop machine. While he and other foot-soldiers went to jail, only one of the bosses, Andy Coulson, ever did.

Little wonder that today he is happy to support hacking litigants, including Prince Harry, not only against the Murdoch company but also against Mirror and Mail papers, by telling what he knows. And though Mulcaire is all but broke he is also engaged in legal action against lawyers who acted for him, and is seeking to overturn his second conviction.

Shadowman is an important book, offering a precious and unique insight into a scandal that is of vast scale and huge long-term significance for the UK. And while it may not be explicitly an apology, it leaves the reader in no doubt about the price Mulcaire has paid for what he did.

Shadowman by Glenn Mulcaire and Joseph Cusack is published by Yellow Press at £6.99 from Amazon. It is one of a series of volumes which together are called Prince Harry’s War: all are written by private investigators or journalists that hacked or blagged Prince Harry but are now allies in his mission to reform the press.