For Better or Worse? Is Nostalgia for the 1970s Really Justified?

As the global right claims the UK has 'gone to the dogs' over recent decades, our intergenerational panel looks at what life in the country really used to be like. Today, Otto English and Issie Yewman

A Boring, Violent Life

Otto English – Born 1969

Mum picked me up outside school and we drove home with her asking me how my day had been. I told her about the music lesson I’d had, the rugby match I’d dodged, and made no mention of the fact that just an hour earlier my 60-year-old headteacher had beaten me with a shoe. I had let another boy copy my homework, we had been caught, and both of us had been violently punished as a result.

It was the late 1970s, I was not yet 10.

Unfortunately, such everyday brutality was commonplace in the era, so I just sucked it up.

I’m not asking for sympathy. I had a very happy childhood and loving, caring parents, and I managed to get over it. But honestly, looking back across the span of the five decades of my life, the 1970s is the one I’d not revisit in a hurry.

That, apparently, puts me in a minority because, according to an Ipsos survey in November, British adults would rather have been born in 1975 than 2025 by a margin of two to one.

The 70s, it seems, appeals to both left and right.

For Faragists, it represents the last gasp of a perceived prouder and more patriotic Britain; when white men were in charge and minorities stayed in their place.

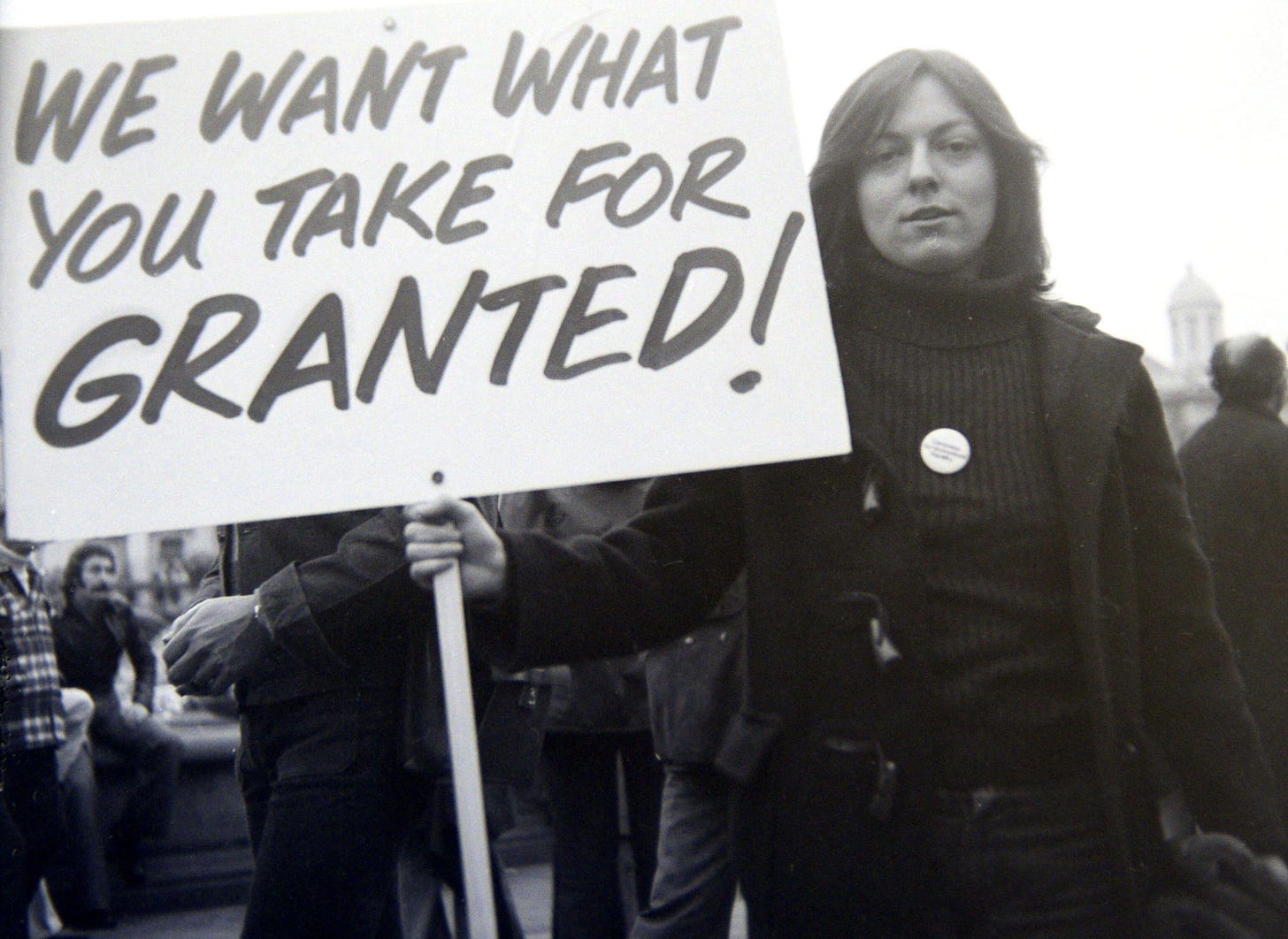

For the left, it seems like an era of optimism, when radical ideas flourished, university grants were still free, unions had influence, and housing was affordable.

Nostalgia lies deep within our species.

Just as the Hellenic poet Hesiod hankered after the lost ‘Golden Age’ all the way back in the 8th Century BCE, so it’s comforting to recall a sanitised 1970s of ABBA, punk, public ownership, platform shoes, Star Wars, and the Silver Jubilee.

We forget that this was also the age in which Jimmy Savile got away with his many crimes, when primetime TV featured racist comedians and The Black and White Minstrel Show, when there was a civil war in Northern Ireland, a genuine terror of impending nuclear war, and when LGBTQ people lived in constant fear.

Those who claim life was more affordable back then forget that inflation hit 25% in August 1975. Very basic items that we take for granted today weren’t on the shelves, and what food there was cost about 30% of a household weekly budget (today it’s about 12%).

Yes, housing was cheaper – but that was because most people did not own their own properties, and 42% of Brits lived in council homes in 1979. Courtesy of the many power cuts and the three-day week in 1974, they often sat in them in the dark.

Technology was in the Stone Age.

Entertainment consisted of tapes and records and whatever was available on the three TV channels which, for most of us, were in black and white.

Life could be very boring indeed, and as just 35% of homes had a landline telephone in the early 70s, there wasn’t even the means to moan about it with someone else.

Holidays were domestic. In 1979, 77% of the population had never left Britain – a figure that seems almost unimaginable in an age when 93% of us have been abroad.

The UK was dubbed ‘the sick man of Europe’.

London was black with soot, and the Bankside Power Station (now the Tate Modern) still belched fumes into the sky.

People smoked everywhere – even on the Tube – and continued to do so until the King’s Cross fire in 1987, because health and safety was abysmal too.

Yes, the unions had power, but we forget how unpopular they were and why they were necessary. Wage equality only arrived in 1975. Employment rights were nothing compared with those that came in the 1990s, and there was no minimum wage.

And those who claim the country was safer then are just plain wrong. All crime was higher, the murder rate was 30% higher than today, and marital rape was legal.

It may be comforting to click on old videos online but I thank the gods of progress that my kids are growing up in this age and not mine.

Despite all our woes, we have come a very long way.

Let’s stop longing for some imagined Eden – where, in truth, middle-aged men beat children with shoes – and make our present work better instead.

Dehumanising Invisibility Versus Insecure Visibility

Issie Yewman – Born 1999

It has been just more than a decade since I was 13, in 2013.

The year before had carried some historic moments with the Olympic Games coming to London and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee – both imbued with a sense of national pride.

Across the pond, Obama had just won re-election, carrying forward the ‘Hope’ campaign that defined much of Gen Z’s early political awareness.

By then, I was in Year 9, playing FarmVille and scrolling on Tumblr, listening to ‘Royals’ by Lorde, seeing Miley Cyrus swing into the zeitgeist on a wrecking ball, and unable to escape my little sister’s obsession with the newly released film Frozen.

Outside of my teenage realm, Britain marked two big moments: the birth of Prince George, the late Queen’s first grandchild and his father Prince William’s heir; and the death of Margaret Thatcher.

In 2013, England and Wales legalised same-sex marriage.

I was deep in the closet then, but that law would later become a right profoundly personal to me.

It often surprises people that Prince George is the same age as the legalisation of same-sex marriage in England and Wales. And that in Northern Ireland, same-sex marriage has been legal for only as long as Covid-19 has existed.

For Gen Z and Millennials, it seems the majority have embraced that legislation and run with it, making our identities more visible and giving older generations the impression of a sudden ‘boom’ in LGBTQIA people. In reality, we have always been here – the difference is that now we are finally seen.

So when Gen Z flirts with the aesthetics of the 1970s – vinyl records, film cameras, retro/colourful décor – it isn’t about yearning for its politics. It’s the desire to escape the relentless churn of capitalism and the overstimulation of modern digital life.

Yet, nostalgia is beginning to be weaponised by politicians.

As we saw in the Brexit campaign, figures such as Nigel Farage and his party draw on a nostalgic vision of the past – one in which women and LGBTQ+ people were denied rights.

The omission of women’s rights protections in Reform’s policies illustrates the instability of progress and the vulnerability of equality today.

Hard-won rights may now be under threat, but a nostalgic yearning for the 1970s would be far worse. For a gay woman, that era was defined by invisibility.

Mothers who were exposed for being queer could be stripped of child custody. Workplaces offered no protection. Society treated our existence as something one should be incredibly ashamed of.

Although lesbianism was never explicitly criminalised under the Labouchère Amendment of 1885, the law denied its existence and left women vulnerable to stigma and discrimination outside formal statutes.

For women more broadly, the 1970s was only the beginning of fought-for rights: the Equal Pay Act came into force in 1975, but maternity rights were limited, and workplace sexual harassment was scarcely recognised. Women were still expected to leave jobs when they married, and trade unions often ignored female workers’ needs.

Growing up, identity politics has fractured us into smaller categories, each marginalised in its own way.

Gen Z have been branded ‘snowflakes’ – a label used by older generations to dismiss legitimate concerns about racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and climate collapse.

Every generation before us, except perhaps Millennials, seems to have worked against us living as our authentic selves.

In 2025, I can hold my girlfriend’s hand in public and bring her home to my family. That visibility is progress – but it lacks security.

When we plan holidays, we still have to check which countries criminalise LGBTQ+ people – there are 65 of them. Recent regressions are beginning to creep in across the globe. Uganda’s 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act introduced life imprisonment and even the death penalty; Italy criminalised citizens pursuing surrogacy abroad – blocking gay and lesbian couples from parenthood; and Hungary banned Pride marches and restricted LGBTQ visibility in schools.

Closer to home, the UK Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling that ‘woman’ means biological sex undermined transgender women’s rights and dragged the UK down ILGA-Europe’s equality ranking.

I fear that, when the time comes to settle down, marry, and call my partner legally my wife, those rights may no longer be secure.

Nostalgia blinds us to the truth: the 1970s were not good, and instability today stretches beyond human rights into the job market and housing crisis.

Far-right populism edges dangerously close to fascism, threatening freedoms we thought would be permanent.

Yes, we are living longer. But living longer is no victory if it means revisiting an era some romanticise – one in which rights were denied.

One in which I could never have lived as myself.

See also multiple recessions, 3 day week, inflation over 20% and interest rates to match. I bought my first terraced house in S London with an interest rate of 12-15%. My children bought their first flats at rates of 2-3%. My repayments as a proportion of income were much higher. Lived on credit cards! It all led to Thatcher

Then there’s the racism, homophobia … and the odd threat of nuclear war. No, the 70s were not a good time - though there was some great music

I was in my 24th year in 1970. This piece is hardly a representative sample or objective evidence. Not what I’d call the fearless journalism from Byline that you don’t get elsewhere. Must do better.

We could make a list of all the things that are far worse today and could be terminal. If the 70’s were so bad it seems nobody has learned anything from the mistakes that were made. One of the biggest and most damaging errors was the adoption and promotion of neoliberalism (started under Callaghan and enthusiastically adopted by Thatcher) and the malign idea of the household economy as the model for the state economy even where a country has its own fiat currency. This was put about by Thatcher as an excuse for cutting government spending on public services etc. and the pernicious myth is still embraced by almost every politician, and journalist, including those who write on Byline, despite the paradigm being demonstrably wrong.