Digital Gangsters: The Inside Story of How Greed, Lies and Big Tech Broke Democracy

In an extract from his book, Ian Lucas reveals how dark forces have interfered in our politics on both sides of the Atlantic

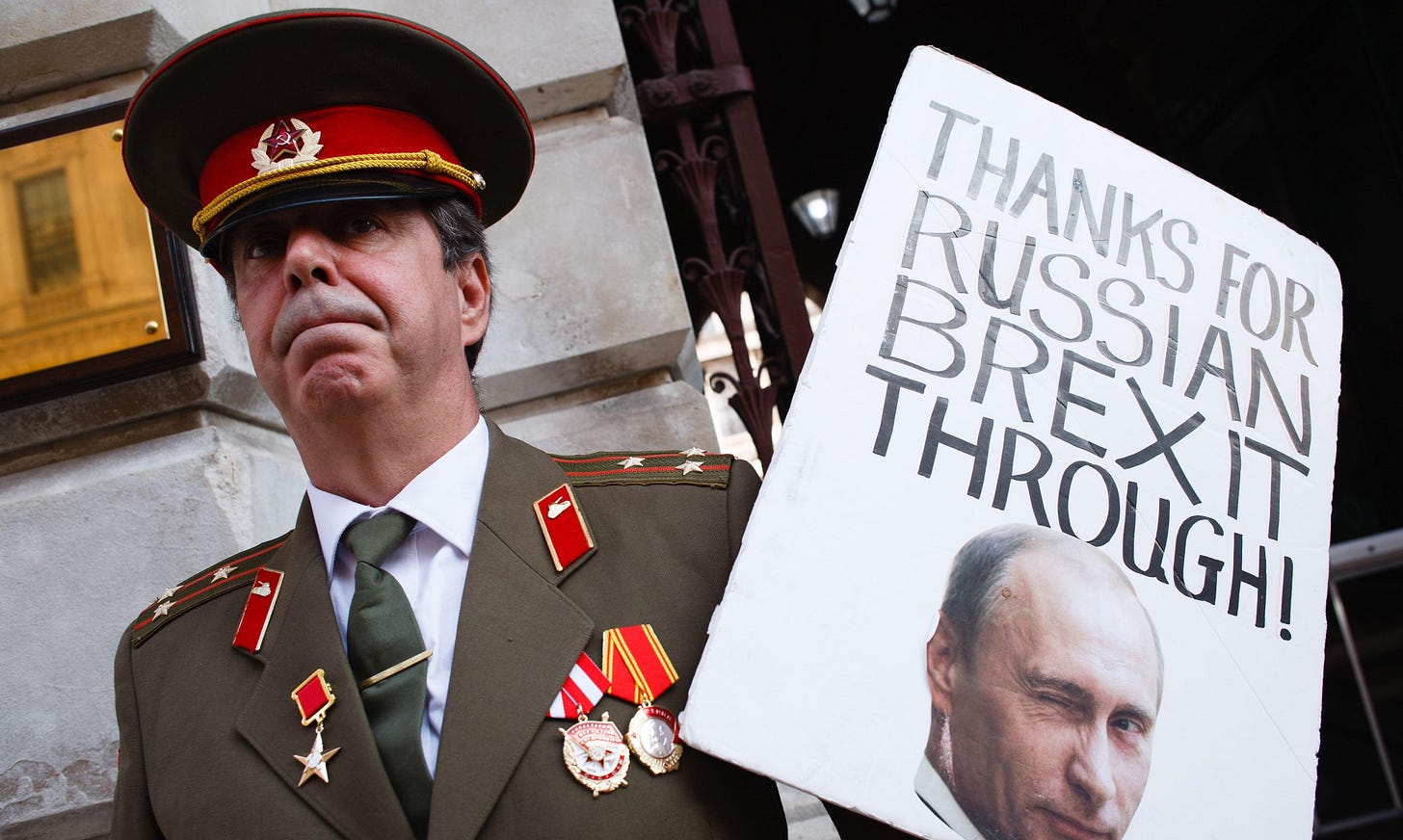

Politics has transformed in the last decade, unseen, at first, even by those at its very heart. As a UK Member of Parliament, I sensed change, even tumult, in the build-up to the 2016 referendum on Brexit. But I did not understand why. The Brexit result and the election of Donald Trump were as shocking to me, a typical member of the political class, as to everyone else.

I wanted to understand.

My journey of understanding began on a visit to Washington DC in February 2018, questioning, with a Parliamentary Committee, senior Facebook executives on Russian political donations and overseas influence and asking how it was that democracy online was unprotected in a way we all took for granted in the real world.

We asked about Cambridge Analytica and Facebook, not knowing that this was the beginning, not the end of the story.

What emerged was a picture of worldwide polarisation in politics, capturing major political parties, nurtured, fostered and grown online, a process gradually revealed but not yet fully understood or controlled.

Digital Gangsters is the story of how I learned what was happening and how crucial it was to democracy that others did too.

It’s a story I had to leave Parliament to tell.

Digital Gangsters

The political shocks in Europe in 2016 were matched in the United States. The election of Donald Trump in November of that year was unexpected to virtually everyone involved in politics that I knew. I remember waking early on the morning after the US Presidential Election, then standing in my dressing gown, stunned, in front of the television in my living room. My stomach felt hollow, recalling my numbness on the morning after the EU Referendum. I would later learn that the two events had much, much more in common than I could ever have imagined.

It was very soon after the Presidential Election that I began to hear more about the issue of online foreign interference in the campaign. This chimed with some of my own concerns about the ability digital gangsters 56 to trace election donations in the online world. The issue had not yet been raised prominently in connection with the EU Referendum. In the UK, there was acceptance that the UK would be leaving the EU and no widespread appetite to challenge the result. Theresa May, who had opposed Brexit before the Referendum, announced that “Brexit means Brexit” and made clear that she saw her role as implementing the result of the Referendum. This had been the central pillar of her campaign for the Conservative Leadership following David Cameron’s immediate, ignominious resignation. She appointed her rivals Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, leaders of the Vote Leave campaign, to her Cabinet, choosing to try to unite the Conservative Party, rather than the country, following the divisive Referendum.

In the US, however, the phrase “Russian interference” entered the political lexicon very soon after Donald Trump’s election. It added to one associated already with Trump himself: “Fake News”.

The announcement that a parliamentary Committee in the UK was to look at “Fake News” caught much attention. That may well have been the intention of Damian Collins, the new Chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee. Damian had taken over from Jesse Norman, who now had a junior ministerial role.

I did not know Damian well but had worked closely with him on two Inquiries relating to Digital Communications and to Drugs in Sport. He was clearly bright but diffident in demeanour. We got on well. He even wrote a discreet note to me, welcoming my shock re-election in 2017.

The 2017 General Election had made significant changes to our Committee but not in the way anyone expected. Labour’s unexpectedly strong showing meant that the Labour membership stayed the same. Chris Matheson, Jo Stevens, Paul Farrelly, Julie Elliott and I joined the existing Tories Simon Hart, Julian Knight and Damian, who continued as Chair. The new Tory members Giles Watling and Rebecca Pow were both easy to work alongside, not at all doctrinaire. The perpetual twinkles in Giles’ eyes testified to his colourful past as a TV sitcom star in the 1980s. Rebecca’s love of gardening later led to her initiating a Committee Inquiry. The SNP member who replaced John Nicholson was, like John, a former journalist, Brendan O’Hara, and his presence created an Opposition majority on the Committee. His prior work experience, together with that of Julian Knight, another former journalist, was useful, particularly with their very different political perspectives.

We were all now looking forward to starting, at last, our Inquiry into “Fake News” with a meaty visit to the land of Big Tech and Donald Trump.

There were early signs that the Government was not delighted with our Inquiry. Damian had wanted to hold evidence sessions of the parliamentary Select Committee in the United States, something he said was unprecedented, and he had approached the British Embassy in Washington to host them. At first we received a positive response from the Embassy, led by Ambassador Kim Darroch, but then we were told the original plan was not possible for logistical reasons, though there were mutterings that the decision was not unconnected to Boris Johnson being Foreign Secretary and resistance from the UK Foreign Office.

In the event, the sessions took place in Washington DC in February 2018, and were hosted by George Washington University. We heard from representatives of Google, Facebook and Twitter. It was important to us that these sessions take place in the US so that we could hear from executives at an appropriate level within the companies.

There was scepticism from within the UK press about our American visit. The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee was a particular target for, apparently, enjoying exotic visits, linked as it was to the arts and sport. John Crace, sketch writer of the Guardian, summed up the prevailing press view of the visit:

“For the first time in parliamentary history, an entire committee had upped sticks and decamped to the US. Quite why they had chosen to do so was not altogether clear.”

But there were good reasons for this particular visit.

Select Committee visits build relationships within the Committee. The Committee team includes not only its members but also its support staff, who were an essential part of the Inquiry. The House of Commons provides excellent research and administrative help for MPs, and Select Committees have staff specifically allocated to them. In this Inquiry, in particular, those staff were absolutely crucial.

The Chief Clerk was Chloe Challender, who coordinated the agenda of the Committee, working mainly with Damian Collins as Chair. Cool and measured, she was a rock at Damian’s left hand during sessions. The main researcher was Jo Willows, who introduced the Committee to, then guided it through, the complex world of social media, Big Tech and disinformation. Jo was bright, personable and incredibly patient. Communications proved extraordinarily complex as the work of the Committee developed and we were fortunate to have the gifted Lucy Dargahi dealing with the enormous media demands we faced. Specially brought in for additional technical expertise was Charles Kriel, who had given evidence to the Committee and who impressed us all with his sharp insights, often delivered to us in the middle of subsequent evidence sessions by text messages with “killer lines” for cross-examination, helpfully sent as the evidence was being given.

The US visit enabled Committee members and staff to meet away from the House of Commons and its constant distractions.

It was essential to visit the United States as we wanted to meet, both privately and in the evidence sessions, US witnesses from the businesses which dominate the tech industry throughout the world, including the UK. We also needed to speak to other tech companies and the international media.

We visited New York initially, meeting Mark Thompson, then New York Times Editor and former Director-General of the BBC, to discuss broadly the approach of the traditional press to news in the age of social media and the specific steps taken by the New York Times, and also to explore the broad US political context for the visit. We took in a visit to the New York site of Google and met with “Now This”, a new Twitter-based media operation, to provide us with a different perspective from that of the tech giants.

For an MP, the visits were an intense learning experience. They educated me for the first time in the pace of innovation taking place in the media world. This was an essential part of the political space in which I worked. It prompted me repeatedly to reflect on how little I knew, as a working politician, about the communications environment in which I was operating then and in the series of elections since 2015. I do not think for a moment that I was alone in the limitations of my knowledge. The constant day-to-day demands of representing constituents mean that it is difficult to find time for reflective investigation of changes which occur outside the political world but impact upon it.

Gazing from the window on the train journey from New York to Washington, I had some time to think about what I was seeing and learning on the visit. Committee members and staff also had the chance to talk informally, and privately, amongst ourselves about the barrage of information we had accumulated in a crowded two days in New York. I remember getting to know Jo Willows, Charles Kriel and Lucy Dargahi better as we talked about what we had heard and thought about what we would be asking Facebook, Google and Twitter in our evidence sessions in Washington. We were building a team spirit.

There was an air of expectancy ahead of these sessions. I had been struck by the level of interest in our inquiry amongst the opinion formers we had met in the US. “Fake News” was news everywhere and the Committee was catching attention as, at that stage, it seemed that no similar questions were being asked by formal, political bodies in the US or anywhere else. Yet the impact of social media on politics was already a real global phenomenon. In the USA, the political world was still adjusting to the tsunami that was the arrival of Donald Trump in the White House.

I met Representative Adam Schiff privately in his office on Capitol Hill with my colleague Chris Matheson who, by fortunate coincidence, had met Adam before on a political twinning visit. Adam was the senior Democrat member of the House of Representatives Select Intelligence Committee, which was to play a vital role in conducting enquiries into Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential Election. We had a useful preliminary discussion about his work in the House of Representatives and learned how Washington political conventions were breaking down with Trump as President. This was echoed by British Ambassador Kim Darroch at a private breakfast briefing with the members of the visiting Committee at the UK Embassy. In a reception, senior journalists, including Alex Thompson of Channel 4 and Jon Sopel of the BBC, gave us their perspective on the extraordinary events unfolding at that time.

The formal sessions with Twitter, Google and Facebook were framed by the relationships built up within the Committee and the trust the members had built up in each other. Damian, who always led off the questioning, knew us all well enough to know that our mutual respect left no place for grandstanding and, generally, that we would not pose a question unless we had something useful to ask. The approach was informal but operated within a framework of a preliminary briefing prepared by the Committee staff and an initial allocation of questions after discussion amongst Committee members.

My personal interest meant that I wanted to talk about foreign donations to political campaigns. This meant that I questioned, particularly, the Facebook executives, Simon Milner and Monica Bickert.

I felt the senior executives of Facebook, Google and Twitter were chosen by the companies to deal with the Committee as politely but unhelpfully as possible. To them, it seemed, we were a distraction from their business. My overall sense was that we were speaking to public relations people, not decision makers. This was to be a continuing frustration for the Committee during the Inquiry.

I enjoy cross-examination. I was an experienced defence lawyer in lower courts around Wrexham and Liverpool. That is a tough learning neighbourhood for a defence lawyer. The decisions were made then by magistrates, lay local worthies who were not predisposed to acquit defendants. Generally, lawyers thought it was more difficult to secure “not guilty” verdicts in the magistrates’ court than in front of juries in the higher courts.

I think of cross-examination like a walk in unknown woods. You never know quite where it will lead. But you do need to prepare. The best questions are the shortest. They give the witness less time to think of an answer. Detail is important too. Often what seems inconsequential can reveal important truth.

The only time I have persuaded a witness to admit in the witness box that they have lied on oath was in Wrexham Magistrates’ Court. The lie was about how many people were present at a crime, not central to the case. The witness said “I lied about that but all my other evidence is true.” Her credibility was destroyed and the defendant walked free.

But I also had the advantage of having been a witness before a Select Committee myself. As a Government Minister, it is one of the toughest parts of the job. Unlike the House of Commons Chamber, where follow-up questions are not allowed, there is no hiding place. So there are strict rules to be followed. Listen to the question. Answer it, no more, no less. Do not volunteer information. If the questioner wants more, they can ask. If you don’t know the answer, say so. Never, ever lie.

I do not think that the Facebook witnesses in Washington stuck to those rules. Simon Milner, giving evidence with Monica Bickert from Facebook, struck me as a cocky witness. I had met him briefly before in Damian’s House of Commons’ office in London. I think it was an attempt to soften us up.

My Committee colleagues and I thought Milner had been chosen to give evidence mainly because he was British. With my local Wrexham misgivings about Facebook at the front of my mind, I asked my questions:

Ian C. Lucas: Mr Milner, earlier you said something very interesting, which I greatly welcome, concerning the election law, because in 2015 and 2017, and in the 2016 referendum, Facebook advertising was extremely important. In those elections, do you agree that it was not possible to establish, as a candidate, where another candidate’s purchase of Facebook’s advertising was bought from?

Simon Milner: I do not understand what you mean. Can you explain further? Can you give me an example in your constituency?

Ian C. Lucas: In my constituency, my opponent can purchase advertising from Facebook in the campaign. It is unlawful for someone to pay for that advertising from outside the UK. Also, all of the information has to be recorded within my particular district. To date, and as we stand today, it is impossible for me as a candidate to check where that advertising was bought from. Do you agree with that?

Simon Milner: Is that also true for the pamphlets that he paid for? Actually, was your opponent a man or a woman?

Ian C. Lucas: No—they have imprints on them.

Simon Milner: Right. But you still do not know how they were paid for, so I am not sure that it is any different from other forms of advertising—

Chair: Can you just answer the question?

Simon Milner: I do not understand what the question is.

Ian C. Lucas: The question is: can you assure me that foreign donors do not pay for campaign advertisements purchased in Britain today?

Simon Milner: I cannot assure you of that, no.

(DCMS Committee, 8 February 2018, Questions 406–410)

This seemed to me to be important. Foreign donations were illegal, in both the UK and the US, and always had been, in order to prevent the very obvious threat of foreign interference in domestic elections. Yet here was Facebook saying, quite comfortably, that it was not possible to be sure that Facebook advertising had not been paid for from overseas.

I continued:

Ian C. Lucas: Do you hold that information at Facebook?

Simon Milner: No—let me try and think about the scenario. So, if somebody is buying adverts to run a campaign in your constituency during the election, we can see the account that has paid for the ads. We will not know where the money has come from to go into that account—

Ian C. Lucas: Do you know whether the account that has paid for the ads is from outside the UK?

Simon Milner: We will have information that will enable us to know who is paying for those ads, yes.

Ian C. Lucas: You know that is illegal—if someone paid from an account outside the UK. Simon Milner: Yes, I am aware of that.

Ian C. Lucas: You are aware of that. Do you prevent that from happening?

Simon Milner: We do not at the moment, but my understanding is that that is a matter for the Electoral Commission to investigate.

Ian C. Lucas: No, it is a matter for you. It is a matter for you, because—

Simon Milner: Actually, Mr Lucas, isn’t it a matter for the person paying for the ad? They have to ensure that they comply with the law.

Ian C. Lucas: No, it is a matter for you. You are not complying with the law either, because you are facilitating an illegal act.

Simon Milner: I have never heard that analysis before. If you have something you can share with us that demonstrates that, I would be interested to see it.

Ian C. Lucas: See, this is the problem, Mr Milner. You have everything. You have all the information. We have none of it, because you will not show it to us.

Simon Milner: As I have explained, Mr Lucas, we are moving forward with new forms of political advertising transparency, which will enable you to have that information.

Ian C. Lucas: So there is a problem.

(DCMS Committee, 8 February 2018, Questions 411–418)

In the first session that the Committee held with Facebook, one of the central defects in the law became immediately obvious. Facebook had no responsibility to give access to information about money spent on elections by their customers and no-one else had the right to access it.

Damian followed up, very helpfully:

Chair: It is extraordinary: if Facebook were a bank, and somebody was laundering money through it, the response to that would not be, “Well, that is a matter for the person who is laundering the money and for the authorities to stop them doing it. It is nothing to do with us. We are just a mere platform through which the laundering took place.” That bank would be closed down and people would face prosecution.

What you are describing here is the same attitude—it is up to the Electoral Commission to identify the person. Even though you know when money is being paid or linked to accounts outside a country, you do not detect it. We hear a lot about the systems, but they are not picking that up at all. Many people would find that astonishing…

Mr Milner…was quite clear that the system is not picking up people from outside one country seeking to place political ads in another. It is not a question of you saying, “Well, we know it’s not going on.” What you are saying is, “It could be, and we’re under no real obligation to call it out when we see it.”

Simon Milner: But Mr Collins, we have not seen in the last general election, during the Brexit vote or during the 2015 general election, investigative journalism, for instance, that has led to the suggestion that lots of campaigns are going on, funded by outsiders.

Chair: You haven’t looked, have you? That is the thing. You have not looked.

Simon Milner: Mr Collins, there is no suggestion that this is going on.

(DCMS Committee, 8 February 2018, Questions 421–425)

To my mind, this evidence was remarkable. We had all heard of the allegations of Russian interference in the US Presidential Election. I had seen Russian-linked individuals, like Alexander Temerko, donating to Conservative candidates prior to the 2015 General Election; this is not to accuse him of wrongdoing but to explain my unease at the process and its possibilities. Such donations were recorded on the House of Commons Register of Interests. Yet Milner was saying that he had never heard of any suggestion, anywhere, that Facebook was facilitating overseas payments by not checking who was paying for advertisements. Interference could be by paid advertisements online and there was no way of checking where those advertisements had been paid from, unless the information was disclosed voluntarily by the candidates for election themselves.

Was I really the only person in the world to have seen this defect in the system? What for many years had been a fundamental rule of election law everywhere – that domestic election campaigns should not be paid for from abroad – had not applied to online campaigning in elections and referendums in 2015, 2016 and 2017 when we had some of the most important, and unexpected, election results in history.

Yet Facebook, one of the richest businesses in the world, was not under any obligation to ensure that the people using the platform were complying with the law with respect to campaigning activity.

At this time, subsequent allegations about Russian interference in the EU Referendum were not yet known to us.

The Committee had decided that Chris Matheson would ask about one specific case:

Christian Matheson: I’d like to ask you about Facebook’s relationship with Cambridge Analytica … Have you ever passed any user information over to Cambridge Analytica or any of its associated companies?

Simon Milner: No.

Christian Matheson: But they do hold a large chunk of Facebook’s user data, don’t they? Simon Milner: No. They may have lots of data, but it will not be Facebook user data. It may be data about people who are on Facebook that they have gathered themselves, but it is not data that we have provided.

(DCMS Committee, 8 February 2018, Questions 446–454)

One of the important roles of evidence sessions is to get facts and statements on the record. Chris did a very good job in this respect on Cambridge Analytica. In essence, the witnesses put forward by Facebook did not tell us the full truth concerning Cambridge Analytica, though we did not know that at the time. We now know that in 2015 Facebook data was passed unlawfully to Cambridge Analytica and that Facebook was aware of that fact. What is astonishing is that Facebook did not use this opportunity to tell us and to say that they had taken action on the matter. We were to find this out within weeks, but not from Facebook.

Importantly, we now had Facebook on the record saying what their dealings with Cambridge Analytica had been. They had not been full and frank with us when they had the chance.

The George Washington University session ended up focussing on Facebook. This was not pre-planned. It was where the evidence led.

After the hearing, I saw that my cross-examination had caught the attention of Now This, the Twitter-based online news agency we had visited in New York earlier in the Committee’s US visit. Overseas interference was newsworthy in the US. Now This had compiled a short film of my questioning, headlined “This Facebook exec admitted to enabling illegal election tampering” and I retweeted it, commenting “Colombo vs. Facebook”, in tribute to the detective played by Peter Falk.

In the UK too, for the first time, the political press had begun to take notice. In a prescient piece, Hugo Rifkind of the London Times wrote:

“For these 11 MPs are the only force in Britain – really, it’s just them – to be concerning itself with just what in hell it is that has happened, lately, to our national conversation. The growth of populism, the Twitter pile-ons, the impact of Russia. The lies, the hate, the division. The fact that your Aunt Beryl now posts really, really mad shit on Facebook and now every family Sunday is a nightmare. All of that. These are the people – five Conservatives, five Labour, one SNP – tasked with figuring it all out.”

Rifkind continued with a shrewd observation, one repeated to me by many US journalists over the months to come:

“When British parliamentarians come up against American tech firms, it is not only the accents that make it strange. One US journalist at the hearing marvels at the MPs’ near universal belligerence. Senators and congressmen worry about campaign funding when facing down big business; MPs have no need. They also have no expectation of getting on telly, so are less likely to grandstand.”

Some had begun to take notice of the Committee’s work. Many more would do so, very soon.

An Uncertain Future

Despite the increasing awareness of the impact of digital campaigns, few law changes have taken place since 2018 and the online, political battleground is much the same now as then. The result is that the electoral law landscape now is unchanged from that which delivered wins for Brexit and Trump and the opponents of populism must win first, under the present system, in order to take the legal steps necessary to safeguard democracy.

Since leaving Parliament, I have been working to increase understanding of the way politics now works but there is so much further to go. I have been astonished how reluctant political journalists are to recognise how much change has already taken place and they continue, in most cases, not to see the wood for the trees.

In the UK, the amount of money now spent online for political advertising has transformed how campaigns are fought.

The biggest challenge remains ignorance and Digital Gangsters is my effort to defeat it. Please spread the word.

Digital Gangsters by Ian Lucas is published by Byline Books at £12.99 and is available only from our online shop