Confessions of a 'Fox Blonde'

Byline writer Heidi Siegmund Cuda reveals all about how her former life as a Fox TV anchor set her on a radical new path

This year, I am celebrating my 10th anniversary of walking out the door of Fox 11 Los Angeles. I even threw myself a divorce party at a Hollywood nightclub upon my unceremonious uncoupling.

I left behind 15 years-worth of Beta and VHS tapes, which are likely preserved in the same newsroom drawers I stored them in, like a time capsule of a woman who was once devoted to her craft.

My only regret was I didn’t take the Anchorman bobblehead that was on my desk. It was of the female character in the film, she too, was a blonde. I used to flick her head as a reminder to not take things so seriously, but I took them seriously, nonetheless.

When I first started in the TV news business, I would have months to pull together an investigation. One of my first series, Girls Behind Bars, I worked on from spring to fall, getting it ready for November sweeps, the vernacular for the quarterly ratings period. By the time I exited the West LA building in 2013, I was producing half-hour specials in a day, investigations in mere hours.

Content that used to air in six-minute segments over a three-day period, became one-offs, clicking in at a minute-ten, tops. YouTube had killed attention spans. It wasn’t all bad. The demand for brevity prepared me for my future career as an unpaid Twitter activist.

Fox Undercover

I was a prolific TV news producer. One of the managers used to tally such things, and whenever I would walk by her desk, she’d say, “You’re a rate buster! You’re producing circles around everyone.”

I’ve always been a devoted workaholic - fingers on a keyboard is how I calm myself, but I nearly produced myself into an early grave.

In 1998, I was a nightlife columnist for the Los Angeles Times, when I phoned in a citizen’s tip to Fox Undercover – the investigative unit for Fox 11 news, the local News Corp affiliate.

I was miffed about a supermarket chain ripping off its customers. Whenever the store would run out of a sale item, employees would fill up the empty space with non-sale items, without removing the sale coupon, thus duping consumers into purchasing pricier items. After it happened to me twice, I called Fox Undercover because I had heard their radio promos.

It turned out the senior producer for the investigative unit used to read my column to find out which clubs were hot, and he invited me in for a meeting.

I began producing TV news that same week, and my first series, Snow Punks – about punk rock and snowboarders – was nominated for an Emmy. I found it easy to adapt words to video, and I went from a paltry print salary to TV dollars.

I was invited by the Los Angeles Times to write a feature on how I made the leap from print to TV, but I couldn’t do it. It just kept coming out traumatic. As a writer, I’m always running with the bulls in the Pamplona of my mind, and I thought it best to stay under the radar with the rest of the great unwashed.

The irony is, when I was in Journalism School at UC Berkeley - I was lucky to be accepted to the Graduate School of Journalism as an undergrad - I was too much of a print snob to even take a TV course. What was on television surely wasn’t news. But when I saw my first TV paycheck, I decided I could make it news.

I was quickly trained to work undercover – killing time in news vans until we spotted our subject, then chasing bad guys around with a camera. The fun part was the long hours of shooting the breeze with the cameramen, until it was time to make our move. One particular cameraman used a roll of duct tape as a beer can holder, keeping a steady supply of cans on ice in a cooler in the back seat.

We were usually tracking people who were con artists, who had cheated older adults out of their life savings, or who had run Ponzi schemes or negative option scams. Some made products that hurt people. Some just didn’t care how they ripped people off. That is how I knew who Donald J. Trump was – his name would surface on pyramid scheme indictments. I would interview the victims.

I found crooks fascinating. Those who would grant me an interview to defend their ‘honor’ knew that I knew that they were scammers. They all seemed to be unloved sons getting back at the world and were miraculously without conscience.

Although it was nice to earn a proper paycheck, six months after arriving in Rupert Murdoch’s lair, I resigned for the first time. As I was producing a Teens On Meth story, I was concerned about the safety of the youths who had let us into their world, and did not want them exploited. When my concerns were ignored, I walked out of the building with my middle finger in the air.

I went back to $50 album reviews, wrote a punk song called Meat is Murdoch, and returned to my pokey nightlife columnist pay. I was saddened, because I knew I had a natural ability to match words to video. A few months later, I was encouraged by my friend Johnny Knoxville, to return to Fox 11, work for the top manager, and put my own spin on things. And I did.

I got back into the TV ring, bringing holy water and a silver cross, and holding both up in the air as I returned to the station. During those years, I worked for a wonderful boss. He pushed back against the worst instincts of New York, and for many years, we had autonomy. They didn’t mess with our number one ratings until later.

During this flush era, I was writing my nightlife column, authoring rap and punk books, and producing news. I used to make my cameramen take off the mic flag when we were out on the scene. Even though I didn’t watch TV news, I knew Fox had a bad reputation. If the cameraman was wearing a t-shirt with the Fox insignia, I would make him turn it inside out. I had to maintain my street cred.

I spent the next decade trying to stay under the radar, avoiding the political bullshittery that takes place in newsrooms – which are essentially the same regardless of the three or so all cap letters in front of the building. A technological revolution was raging, but not in our newsroom.

Fox was, of course, extra. I used to tell my daughter that sexual harassment was just part of my job description, and when she told me that didn’t make it right, I was at a loss for words. I had never known any differently. This was years before the ‘#Me Too’ movement. It was the norm for men to behave badly.

The women who went to Human Resources to make a report were dead women walking. The job of HR was to protect the company, which meant protecting the patriarchy.

I managed to avoid the more lascivious characters in the newsroom by playing dumb. One of my greatest achievements. When I would feign ignorance, and act as if I wasn’t picking up on what they were transmitting, they would move right along.

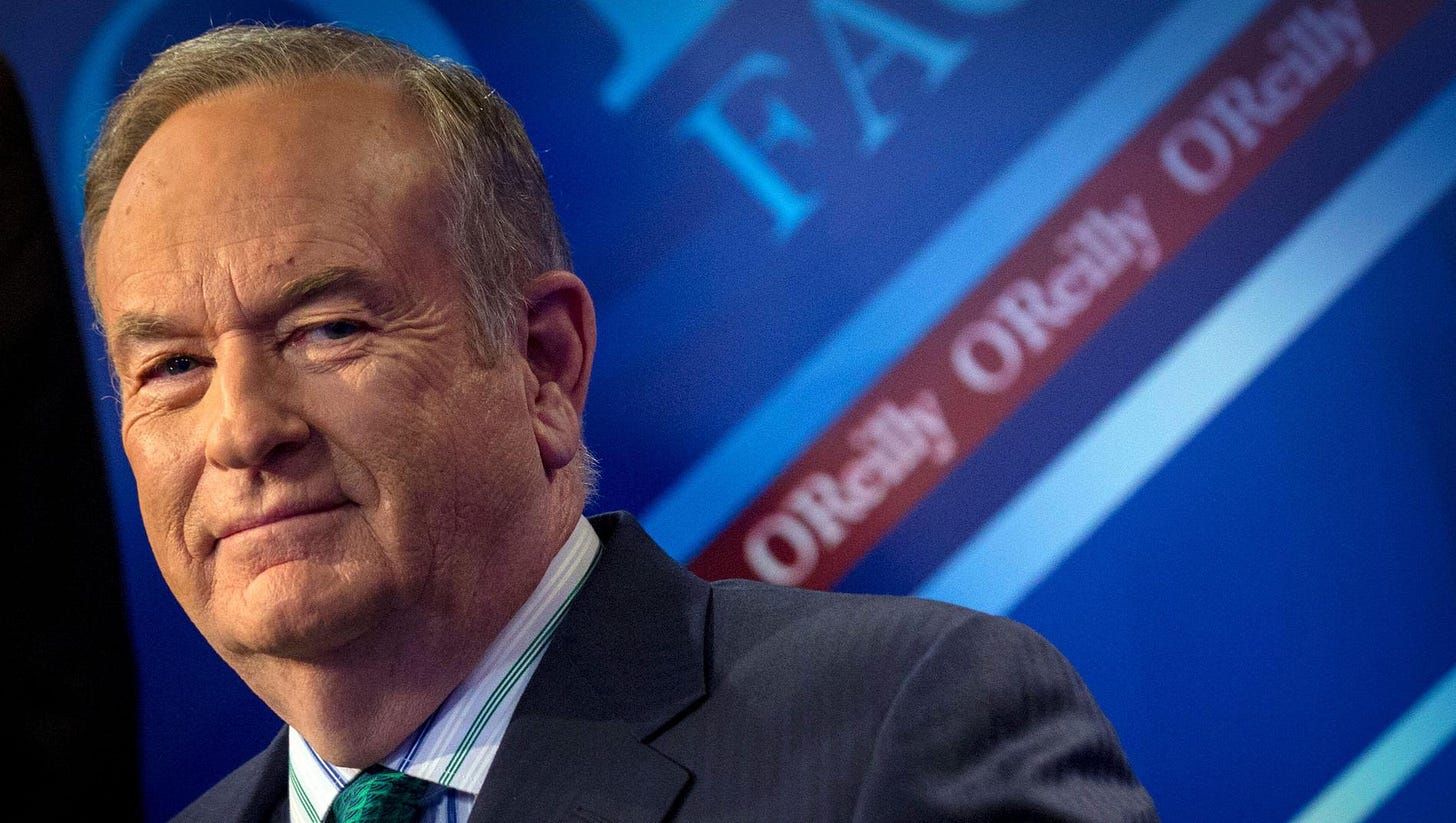

That did not work for Bill O’Reilly, who I had the displeasure of meeting when I was 24. I was working as the associate editor of Hollywood Magazine, when I was tasked with interviewing the anchorman as he made the jump from ABC to Inside Edition.

We met in a cramped hotel room, and I recall our chairs being so close together that his manspreading created no room for my knees. I had to tuck my legs under my chair. As he swung his long legs back and forth during the interview, knocking directly into mine, he had a lecherous twinkle in his eye. I did the only sensible thing a girl could do in that situation.

I lobbed him three softballs and then went for the jugular.

“How does it feel going from a real newsman to infotainment?” I asked.

I obliterated that lecherous twinkle with a hardball, and he turned into a viper. He was no longer interested in this young chippie in a pink sweater twinset, and the interview abruptly ended.

I would refine my act as time went on, and playing the dumb blonde came in handy when I was trying to sneak things on air.

One day at the station, I was asked to go round up a few Nazis - always good for a ratings sag. I made some calls and found one who was aggrieved that there were “no scholarships given to people for being white”. It was absurd.

Instead, I pitched my boss on filming the Punk Voter Tour, which was also the Rock Against Bush Tour. I just didn’t bother to include the second part of the title in the pitch or final cut, which featured Dead Kennedy’s frontman Jello Biafra wearing a Fuck War tshirt, which the editor and I decided not to blur. Biafra, who I knew from the punk scene, laid into me for working for Fox. I told him, “I don’t watch television, and I only can speak for my work, and I do good work.” He seemed satisfied with that response.

After the segment aired in the LA Market and got picked up on all the O & O’s (owned and operated affiliates), a producer came up to me and said, “You know, that’s the Rock Against Bush Tour.”

I turned neanderthal, grunting “Huh? Uh.” And shrugged.

But I will tell you, that segment turned the tide on attitudes to the war. Up until that aired, no one was protesting the Iraq War. After that segment aired, protests sprung up everywhere. That was the power of working in the second biggest market in America.

Another victory during those years was getting the diet supplement ephedra taken off the market in response to an 11-part series. The pills were killing people, and were part of a GOP-led scandal long since buried.

For me, it was always about the work. And I tried to do good work within the system for as long as I could. That was something I learned from Ice T. We wrote a book together that was published in 1994, and in it he said that one of the greatest ways to affect change was to work within the system, and I took that to heart.

I did a lot of serious investigative reporting, but I also produced features on music - and even a series called Foxx Roxx, which documented Hollywood’s amazing nightlife in the early 2000s.

Once, when I was out at a carnival producing a story on Chuy the Wolf Boy – a guitar-strumming hirsute – a viewer asked me why I wasn’t on camera. I explained that I was the producer, and he still seemed confused. I told him, “I come up with the story ideas, go out and get the story filmed, write the script, and then turn it over to an anchor to track, and then edit the package.”

His eyes got wide, and he said, “Ohhhh, so you’ve got the Big Braaaaains.”

How my Big Break Broke Me

There was a lot of freedom being behind the camera. The producer calls the shots. When I was out filming the annual Blessing of the Cars – where lowriders and rat rods from all over the state came to be blessed by a priest – I refused to allow my cameraman to film a pitbull attacking a horse. Neither dogs, nor horses were allowed at the event, but they showed up anyway. If he filmed it, the event would have been killed – as the video would’ve been exploited for ratings all across the network.

I could get ratings without having to hang in the gutter, and I did.

By the time I had been producing for the better part of 13 years, I got a new boss who told me to go ahead and start doing the work for me. He put me on camera.

I had gotten tired of handing my scripts over to anchors to narrate as their own, because I felt it diluted the product. I had no on-camera training, so I had to learn via baptism by fire.

And suddenly, I was alone in my newsroom. There was a quiet denial about me getting a break. It had never happened before in the history of corporate local TV news that a woman in her 40s got a break. As I was doing my cut-ins from the newsroom, I was studiously ignored. Only one anchor whispered before my live shot, “Smile with your eyes.”

The truth is, a TV newsroom is a lonely place at the best of times. And these were not the best of times. Staff numbers had been cut to the bone during the Great Recession, and over-producers like me could not get fired, because I was a content provider.

I would work on longform investigations, write sweeps pieces, write day-of-air scripts, produce a business and economic series, create chyrons (electronically generated captions), graphics, and write speeches for the General Manager in my non-spare time. I was always go go go go, a spinning top that just kept spinning.

Now that I was presenting news on air, I was no longer under the radar, and the knives came out.

It’s a boring story, but the upshot is – to keep me on air, I was made very expensive and used as a pawn in negotiations between employees and management. The purse string guards in New York had all the warmth of Kim Jong Un, and that made me a liability. I was taken off air during negotiations, and returned to writing scripts for others to front.

The stress of an already stressful job was getting to me. I was waking up in the middle of the night screaming, gasping for air, as my heart worked overtime to handle the stress.

My boss would pass me in the halls and say, "We're really going down the rabbit hole now."

I didn’t know then that it would turn out to be a blessing. Narcissists were doing for me what I could not do for myself. I would get out from the Fox web while still in the Before Times. National Fox is now a fully engaged weapon of mass democratic destruction.

Before I resigned, however, I had one final act. I ran an underground campaign to oust a newsroom bully from a position of abusive power and won. But in the dark corners of the parking garage, the bully hid behind pillars, leaping out to scare people into giving him his position back. They caved, he regained power, and I knew enough about Sun Tzu’s The Art of War to know that if a dictator, even a petty one, regains any power, that spells doom.

My final week in TV news, each night, I would wake up screaming like Frank Sinatra in The Manchurian Candidate.

My doctor diagnosed me with an anxiety mood disorder and gave me a note to take time away from work. In 15 years of reporting news, I'd never called in sick. Reporters don't call in sick. They show up. So I kept going to work.

But on that one day in 2013, when I walked out of the building for the last time, I went to a bird sanctuary. I wasn’t the first anchor who nearly cracked.

“I feel connected to all living things, to flowers, to birds.... even to some great unseen living force,” said Howard Beale, the anchor who cracked in the 1976 film, Network

I had no path ahead of me, I just knew I wasn't going back. I entered a six-week work stress therapy program that offered me salvation from an increasingly dystopian 24-hour news cycle. It also gave me perspective and tools to mitigate stress, and how to better respond to triggers.

About three weeks into the program, my producing colleague at Fox, the only other investigative producer left in the building at that time, died of unnatural causes.

I learned that anxiety doesn't kill you. But anxiety unchecked becomes stress, and stress can kill you.

I diagnosed myself with Post-Traumatic News Syndrome, and it would take time to recover. I had been infected with the callousness that comes with that type of work years earlier. I reflected back on the exact moment I became aware that I was changing.

I was in an edit bay, waiting for the only machine in the entire building that could transfer a particular type of tape. I was watching someone else’s video while waiting. It was a woman who had a botched lap-band surgery and now risked dying. I quipped to the editor, “Why didn’t she opt to get her eye bags done at the same time?”

I heard him say, “This business makes people so cold.”

I felt that. I was turning cold.

Re-Invention

The day before I was supposed to go back to work from my medical leave, I ran into a manager at my colleague’s funeral. He said, "Will I see you tomorrow?" I looked at him sadly and shook my head.

After my six-week work stress program was up, I officially resigned from my position in TV news. The station would have to continue its death spiral without me, and I embarked on a super scary and precarious journey of independence.

I had no blueprint. The freelance writing world no longer existed. The print reporter as vocation had been effectively killed off by the Huffington Post and Fiverr.

It would take me time to recover, and although rare, I still get periodic Fox tremors - nightmares where I'm back in the newsroom, nightmares that always end in gore-fests.

The last one I had, I was in the building, and I had a headset on and could hear what everyone was saying. I knew I had to get out of the building. It was unsafe. So I walked outside into the street, and then I looked up, and saw a news van flying into the building. I realized it was an act of terror, and I ran back in and grabbed my investigative mentor and pulled him out of the rubble to safety.

I woke up shaken. Little did I know that ten years from that moment, I would be fighting a much bigger battle, and able to do so, because of my experience and training.

I think back to those days, and will never forget the parting words from a veteran female manager. “You’ll be back,” she said.

I assured her she would see me in the bread line first.

As it turned out there was a much bigger fight ahead. When in the fall of 2016 I learned from my former Fox mentor that Trump was going to win the presidency, I realized I was a woman with a particular skillset, unshackled by a corporation, who was in a unique position to speak truth to power.

I pressed send on my first anti-Trump blog - Dooshbaggery and Other Things I Resigned From - and never looked back.

Heidi Siegmund Cuda is an Emmy-award winning investigative reporter, who writes about politics and culture for Byline Supplement and her Bette Dangerous Substack. She cohosts and produces RADICALIZED Truth Survives, an investigative show about disinformation. Her screenplay, Zombie Newsroom is based on a true story, and she just published the novella, Fox Undercover.

So raw, real and courageous. Thank you Heidi!

Thanks, I enjoyed your article.