Byline Times Print Edition: ‘If These Crimes Cannot Prompt Self-Reflection and Reform, What Will It Take?’

This year’s Casey Review into Britain’s Metropolitan Police starkly revealed how a culture of ‘defensiveness and denial’ has allowed wrongdoing to flourish – but will this be a turning point?

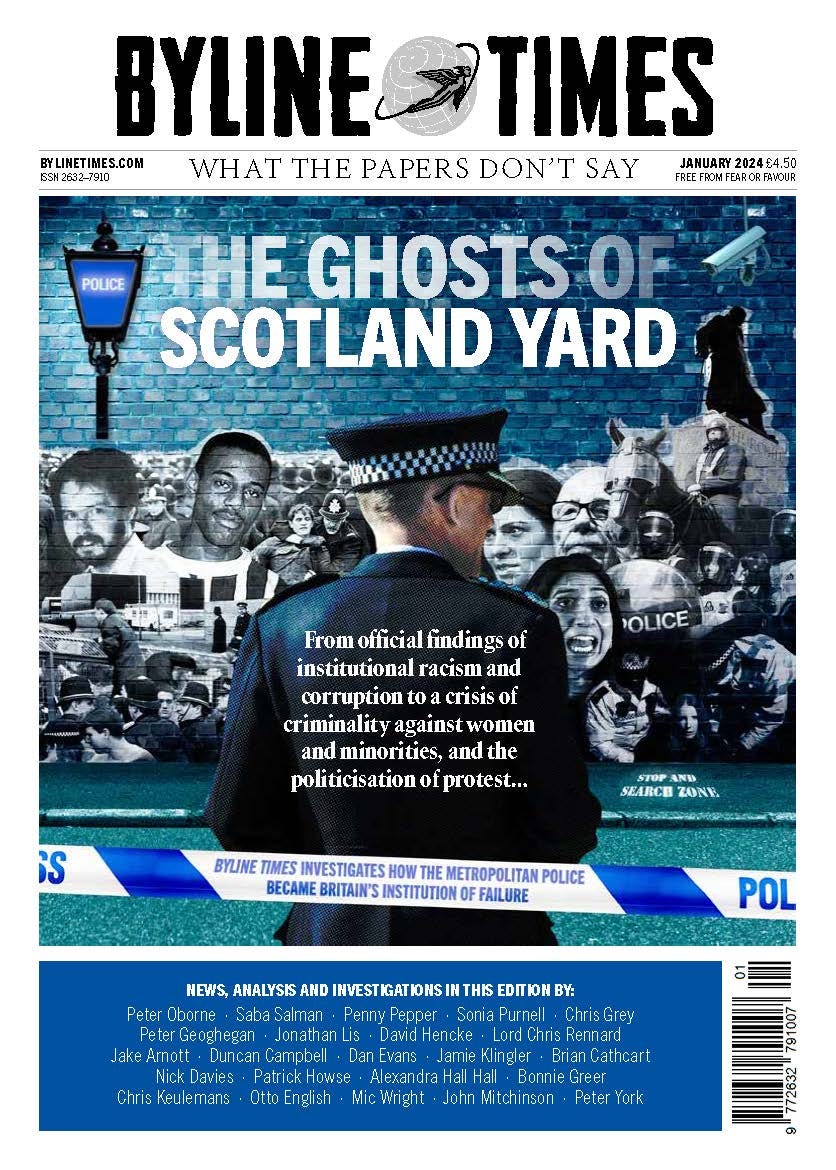

The new Byline Times print edition investigates how the Metropolitan Police became Britain’s institution of failure. Joining the dots between the historic and the current, and exploring the links between corruption, complicit elements in the media, and the force’s politicisation – as the established newspapers can’t or won’t do – this new issue exposes the extent of the institutional decay that is being ignored, while our governing politicians and press pursue their own narrow interests through ‘culture wars’.

The following article, by Byline Times Editor Hardeep Matharu, is published in the latest edition

On the afternoon that the findings of the Daniel Morgan Independent Panel were revealed in 2021 – which concluded that the Metropolitan Police’s investigation into the 1987 killing of the private detective had been marred by “institutional corruption” – its Assistant Commissioner wasn’t convinced.

Baroness Nuala O’Loan’s independent review into the unsolved murder found that “concealing or denying failings, for the sake of the organisation’s public image, is dishonesty on the part of the organisation for reputational benefit” and that “this constitutes a form of institutional corruption”.

But at a press conference a few hours later, Assistant Commissioner Nick Ephgrave said “I don’t accept that the Met Police is institutionally corrupt in the broadest sense”. Why? Because “it doesn’t reflect what I see every day”. He also told journalists, somewhat bizarrely, that it was “a new term that’s been coined” and not one “people are familiar with”.

It was in stark contrast to Baroness O’Loan’s conclusion: that “the historical intelligence examined does not reflect a ‘rotten apple’ model of corruption” but “is indicative of systemic failings, including the existence of a corrupt culture”.

The Panel’s finding, of course, followed some years after the conclusion of “institutional racism” by the 1999 Macpherson Inquiry into the investigation of the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence six years before.

But Ephgrave’s almost knee-jerk defensiveness was indicative.

A few months on, Baroness O’Loan told the London Assembly that such statements, and others from the Met’s leadership, “illustrate exactly the problem that we have been describing”. She said the country’s largest police force had “not responded honestly” to the public or to Daniel Morgan’s family about the serious failures highlighted in the Panel’s report, and that this amounted to a “betrayal” of both.

“The Metropolitan Police has placed concern for its reputation above the public interest,” she said. “There has been dishonesty for the benefit of the reputation of the organisation and that is institutional corruption, and the statements made on behalf of the Met have continued to lack candour, even after the publication of our report.”

This concern for its reputation over transparency and rooting out wrongdoing in its ranks is a core failing that this year saw the force also found to be institutionally misogynist and homophobic.

It points to two serious shortcomings: a lack of any real scrutiny and oversight of the Met demanding accountability and change at the £4 billion public institution; alongside an entrenched refusal of the force to examine itself and accept its structural failings.

All of this was set out in shocking detail in this year’s Casey Review, commissioned by the Met following the sentencing of serving Met Police officer Wayne Couzens for the rape, kidnap and murder of Sarah Everard in 2021. It was a case that caused outrage – but one which has unfortunately seen others involving sexual violence against women follow.

In January, Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley made the extraordinary admission that two to three criminal cases against police officers were expected to go to court every week in the months ahead. That we have reached this level of criminality at the hands of the police is a truly shocking state of affairs for our democracy; the rule of law. And yet, it is not an issue that seems high up on the political or press agenda.

While Rowley said he accepted the Casey Review’s findings of institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia in the Met, he also told Baroness Casey he is “confident that the service of today is changing” and that “we are more diverse, more tolerant, more culturally aware and more sensitive to the impact of our work on communities”. (According to the review, Met officers are 82% white and 71% male and the majority do not live in the capital).

In press interviews, he clarified why he would not use the term “institutional” to describe the nature of the Met’s issues: “This is about an organisation that needs to become determinedly anti-racist, anti-misogynist, anti-homophobic… I’m not going to use a label myself that is both ambiguous and politicised”.

The Casey Review’s findings were staggering.

The Met isn’t “fully alive to the risk” that policing can “attract predators and bullies – those who want power over their fellow citizens, and to use those powers to cause harm and discriminate”. Despite “heinous crimes” perpetrated by serving Met officers “it did not stop to question its processes” and has “no systems in place” to ensure staff and officers adhere to ethical standards.

“The organisation has a ‘we know best’ attitude,” the report states. “It dismisses external views and criticisms, and adopts the attitude that no one outside the Met can understand the special nature and unique demands of their work. This hubris has become a serious weakness.”

“Defensiveness and denial” is listed as another failing: “The Met does not easily accept criticism nor ‘own’ its failures… Instead, it starts from a position that nothing wrong has occurred. It looks for, and latches onto, small flaws in any criticism, only accepting reluctantly that any wrongdoing has occurred after incontrovertible evidence has been produced.”

It also highlights the Met’s “strong tendency to look for a positive spin, which allows the organisation to move on” and its approach of blaming “individual ‘bad apples’ rather than pausing for genuine reflection on systemic issues”.

It found scrutiny of its performance is weak, with HMICFRS an inspectorate not a regulator, and that the Mayor's Office for Policing And Crime does not provide the strategic oversight the Met needs.

According to the review, the force must be “more transparent with the public, with local authorities and MPs, by explaining their decisions and the reasons for them, and by acting with greater candour” so that the Peelian policy of ‘policing by consent’ – which Britain is known for – can be restored.

For Baroness Casey, the reforms required of the Met are “on par with the transformation of the Royal Ulster Constabulary to the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the end of the last century”. Despite this, and some initial publicity around her report, the issue hardly dominates news coverage in the established press.

But it must. Because all of these failures are known about. Have been known about for years and years. It is the culture and poor management of the Met that has allowed wrongdoing to persist by its refusal to hold a mirror up to itself in any meaningful way. This approach has cost and ruined lives. This is why we live with the dark normalisation of serving police officers regularly charged with serious violent and sexual crimes today. And why minorities, by default, are deeply alienated from the key pillar of our society meant to keep them safe.

As Reverend Mina Smallman, the mother of two murdered daughters and another victim of Met officers’ crimes, told the Casey Review: “The strides and the windows that we’ve been able to open into this institution have not come about because of the police’s desire to change. It’s come about on the backs and the tenacity of people of colour and women, and that’s not the way we’re going to affect real change. If you’re constantly trying to cover up the cracks then you’re never going to address anything.”

Baroness Casey’s summation is strikingly simple: “If a plane fell out of the sky tomorrow, a whole industry would stop and ask itself why. It would be a catalyst for self-examination, and then root and branch reform. Instead the Met preferred to pretend that their own perpetrators of unconscionable crimes were just ‘bad apples’… if these crimes cannot prompt that self-reflection and reform, then what will it take?”

It is a question the Met must be made to answer. There is nothing to currently make it do so.

Hardeep Matharu is the Editor of Byline Times