Busting the Launch Pad: Elon Musk and the Myth of the Secret Genius

In light of Musk's mishaps with his SpaceX launch and Twitter takeover, Brian Klaas' insights into the social and psychological dynamics of self-proclaimed geniuses are more timely than ever

This was originally published in Brian Klaas’ The Garden of Forking Paths. If you enjoyed this post or would like to support his work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscriber to his excellent substack.

If he’s super rich, he must be a super genius.

That conclusion is a cognitive mistake many continue to make when they encounter a seemingly incongruous state of affairs, such as Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, behaving like an irrational idiot. And yet, behave like an idiot he does, day after day, a public jester who can buy the world’s most expensive jewels or light $44 billion on fire, but hasn’t yet found a shop to sell him self-awareness or common sense.

Elon Musk is part of a small class of extremely rich people who are rich partly because they’re effective at making others think they’re Secret Geniuses.

Other alleged Secret Geniuses are constantly in the news these days: Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos (heading to prison); Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX (probably heading to prison); Adam Neumann of WeWork (who produced a spectacular financial collapse); and Mark Zuckerberg of Meta (who has, so far, poured $30 billion into a metaverse that looks like a PlayStation 2 game from 2001).

Likewise, whenever Donald Trump did something extremely stupid, his supporters would often claim that people simply didn’t understand his “four-dimensional chess” game. Just wait until he checkmates you! The election forecasts must be wrong, because they didn’t understand that his Twitter outbursts were secretly winning over swing voters. But it was all a mirage. (The simplest explanation was the correct one: he just wasn’t that smart and he had no self-discipline because he was a narcissist).

But those who doubt The Secret Geniuses, or express scepticism about their methods or their madness, must simply not be smart enough to see the bigger picture. If you question the Secret Geniuses, then all you’re doing is exposing yourself as one of the stupid proles, someone unable or unwilling to Think Big.

If you can’t understand why it was secretly smart for Elon Musk to pick a fight with the advertisers who used to give Twitter billions of dollars of annual revenue, well then you’ll just have to live with the fact that you’re too conventional and too conformist. We pity you for not seeing the bigger picture, they say.

Why are so many people seduced by these rich hucksters?

The first problem is that many still falsely believe we live in a meritocratic society, in which riches are purely a marker of talent rather than of luck or generational wealth.

If someone is a billionaire, they must be a genius. But there are serious reasons to doubt that claim. Wealth is not normally distributed, like height. While there’s never going to be someone who is even 3x shorter or 3x taller than you, Elon Musk is about three million times richer than the average American. That means that the super-rich are extreme outliers, and that creates some major statistical irregularities that are not tied to talent.

Talent, in the way that it is often defined within Western society at least, is, like height, normally distributed. That creates a mismatch. Someone who is marginally smarter than you could become 100,000 times richer, rather than marginally richer. (It’s also clearly the case that people vastly less smart than you could become substantially richer. See: Trump, Donald, and especially, Trump, Donald Jr.).

Fat Tails

This is the world of what are sometimes called “fat tails,” where the bulk can be found at the extreme. In the sea of poor people, a few grotesquely rich people bob on the top while millions drown in misery.

A recent research study, involving a collaboration between physicists who model complex systems and an economist, however, has revealed why billionaires are so often mediocre people masquerading as geniuses. Using computer modelling, they developed a fake society in which there is a realistic distribution of talent among competing agents in the simulation. They then applied some pretty simple rules for their model: talent helps, but luck also plays a role.

Then, they tried to see what would happen if they ran and re-ran the simulation over and over.

What did they find? The most talented people in society almost never became extremely rich. As they put it, “the most successful individuals are not the most talented ones and, on the other hand, the most talented individuals are not the most successful ones.”

Why? The answer is simple. If you’ve got a society of, say, 8 billion people, there are literally billions of humans who are in the middle distribution of talent, the largest area of the Bell curve. That means that in a world that is partly defined by random chance, or luck, the odds that someone from the middle levels of talent will end up as the richest person in the society are extremely high.

Look at this first plot, in which the researchers show capital/success (being rich) on the vertical/Y-axis, and talent on the horizontal/X-axis. What’s clear is that society’s richest person is only marginally more talented than average, and there are a lot of people who are extremely talented that are not rich.

Then, they tried to figure out why this was happening. In their simulated world, lucky and unlucky events would affect agents every so often, in a largely random pattern. When they measured the frequency of luck or misfortune for any individual in the simulation, and then plotted it against becoming rich or poor, they found a strong relationship.

Here are the plots for riches compared with lucky events, which as you can see are strongly correlated.

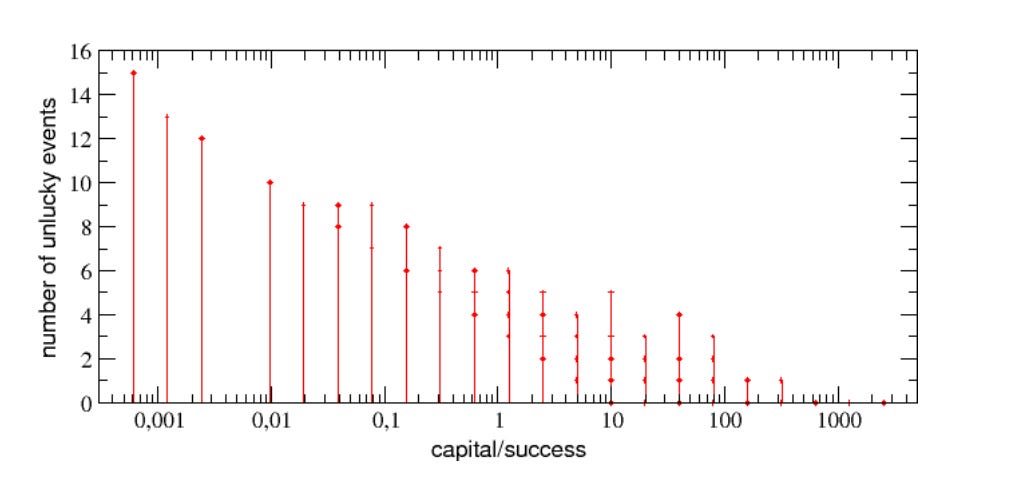

And here are the plots with unlucky events:

(This data correspond pretty well with what my late grandfather’s advice was on how to be successful in life: “avoid catastrophe.”)

The authors conclude by stating “Our results highlight the risks of the paradigm that we call “naive meritocracy", which fails to give honors and rewards to the most competent people, because it underestimates the role of randomness among the determinants of success.”

Indeed.

Perhaps this is something you’ve long suspected, and there are plenty of studies that have made similar arguments, but this research shows that with a few relatively simple assumptions, you can recreate our real-world distributions, showing how randomness and luck are crucial to success.

Some billionaires are smart. All have been extremely lucky.

But there’s something else going with the Secret Geniuses. Venture capital is a world where the most effective way to get investors is to convince them you’re different—a one in a million visionary. This phenomenon is amplified because many investors are assuming that most of their bets will fail, but that every so often, one of their bets will produce a fat tail that leads to vast riches, as was the case with Facebook. When that happens, all the previous failures become meaningless, because the billions produced by the one success dwarfs the millions poured into the businesses that collapsed.

Everyone in venture capital is looking for their Secret Genius.

So, what’s the rational thing for an ambitious, money-obsessed narcissist with a start-up to do? Sell them one. Give them the myth they want to believe.

Buying into the Myth

Elizabeth Holmes, I suspect, knew she wasn’t really a Secret Genius, and could admit to herself that what she was selling was fraudulent, a failed technology dressed up in technical language that would trick people into believing it was the real deal, with the help of her confident smoke and mirror show. Elon Musk, I suspect, is high on his own supply and takes it as granted that everyone else (and especially his critics) is much stupider than he is.

But whether the Secret Geniuses believe they are geniuses or not doesn’t really matter. What matters is what their investors think.

That dynamic creates strong incentives for already eccentric narcissists to indulge their worst impulses. Set yourself apart from the crowd in ways that dazzle people and you can create a self-fulfilling prophecy with other people’s money. Using signalling theory, the Secret Geniuses develop ways to stand out, hoping it will convince doubters that they just don’t understand the genius (this is likely why Mark Zuckerberg has a terrible haircut mimicking Julius Caesar and always wears the same shirt).

Here, the computer model world discussed above deviates from reality. Yes, luck and random chance do play a major role in success. But in the world of the Secret Geniuses, a certain talent is being selected for other than competence: the ability to convince people that you are a Secret Genius. On that score, Elon Musk, Elizabeth Holmes, and Sam Bankman-Fried are off the charts.

But this phenomenon isn’t just a problem for venture capital and finance.

Power, like wealth, is a magnet that attracts dangerous hucksters, and then rewards them. As I’ve written in my latest book, Corruptible, three traits known as the Dark Triad tend to, unfortunately, produce success. The three traits (Machiavellianism, narcissism, and being a psychopath) are disproportionately correlated with obtaining power, and by extension, wealth. I’ll leave it to your judgment to determine how many of the three apply to, say, Elon Musk.

Then, there’s overconfidence and over-promising. For whatever reason, we almost never punish rich people who over-promise and under-deliver.

So much in the Trump era was going to be announced “in two weeks” that it became a joke to refer to something that would never see the light of day. Likewise, Elon Musk is his biggest hype man, promising brain implants that would revolutionize the ways we live, or saying that he’s building a tunnel that will transport people between Washington and New York in 29 minutes. (Instead, his tunnelling venture, the Boring Company, has mostly ghosted government, and its one viable project in Las Vegas is literally a tunnel lit up with futuristic lights in which cars drive slowly, making it less efficient than a tram).

There are also reasons why, due to a concept known as evolutionary mismatch, we reward overconfidence. (If you’re interested, this paper published in Nature about a decade ago is the best piece of research I’ve seen written about it). This pervades our society, even in the most seemingly meritocratic realms.

Promising the Moon

The Gates Foundation, which rewards grant money to applicants, subjected its awards to scrutiny and found something fascinating. The grant applications that promised the moon were more likely to get funding than those that promised more modest, realistic results. But when the proposals actually got funded, those that over-promised frequently delivered similar results to those who accurately depicted their research.

The language used mattered a lot. If someone referred to their research as “innovative,” or “game-changing,” for example, they would be more likely to get funding than if someone accurately depicted it as an important, but incremental step toward better knowledge. And guess who tended to use over-confident language that promised the moon?

Men.

The study therefore showed that one reason for gender bias in grantmaking isn’t due exclusively to sexism, but also to the fact that men were more willing to sell a big idea with more expansive, over-confident promises.

Now, imagine that instead of the more sterile world of Gates Foundation grant applications, you’re sitting around a table in Silicon Valley with a bunch of super-rich tech bro investors who are looking for their Secret Genius. Who do you think gets the most money?

There’s one final phenomenon worth mentioning, as I think it explains a lot of what’s going on with Elon Musk. When you enjoy a level of success that makes you the richest person in the world, it’s impossible not to start to believing that you and your ideas have some magical qualities to them. (And Elon Musk has had some legitimately very good ideas at various points in his career).

But most real geniuses have one or two extraordinary ideas in their lives. If you’re doing theoretical physics research at the Large Hadron Collider, you may toil for decades hoping to discover a true stroke of genius, a new particle, or a finding that upends the ways that we think the universe works. If you discover the Higgs Boson, though, you don’t instantly think that means you’d automatically be great at running a social media empire.

Elon Musk has had a few brilliant ideas, and he thinks that means he now has an endless supply of them. Reality has shown that he does not.

True geniuses are humble. Those who fashion themselves as Secret Geniuses are not.

So why do Secret Geniuses who strike it rich so often end up destroying themselves with their own idiotic impulses?

What happens when you have an overconfident narcissist with a lot of power and even more money? The answer has a parallel with authoritarian regimes. A few months ago, I wrote an article for The Atlantic, explaining “The Dictator Trap,” in which authoritarian leaders miscalculate because they purge anyone who disagrees with them. Over time, the yes men survive, while those who tell hard truths get weeded out.

A similar dynamic exists for narcissistic billionaires like Elon Musk. Nobody seems to have told him that some of his ideas for Twitter reform could work, but they’d work much better if there was a strategic rollout, if he didn’t alienate his key users and his advertisers, and if they were more than the tweeted out whims of his overconfident brain.

Why is he falling into that trap? Because people that criticize Elon Musk with hard truths get fired by Elon Musk.

Now, given that this newsletter is called “The Garden of Forking Paths,” about all the possible worlds we choose in life, I close with a thought of a path not taken. Decades ago, when Elon Musk dropped out of academic life, he applied for a job at Netscape, which was one of the early corporate pioneers of the internet. Musk never heard back. The world would very likely be a different place if they’d offered him the job.

Instead, Musk went down the path of the Secret Genius, and, for better or worse, we’re all stuck with him on that path.

About half the content of Brian Klaas’ newsletter is free, but do consider supporting his work with a paid subscription